Postscript: This was written in fits and starts, spaced out across about five months—usually coinciding with Wizards of the Coast previewing a new Magic: The Gathering expansion and releasing the associated web fiction. As usual, one of the motivators of this "exercise" is the idea that I can apply to myself the parental logic of forcing a child to smoke an entire pack of cigarettes after catching him lighting up in the garage.* It's worked before, and the results were usually something I could live with. This time...I'm not so sure.

For the Magic: The Gathering fan/addict (what's the difference?) who happens upon this writeup, I suspect it'll be so much catnip. For the person who's never thought about or spent any money on the damn cards, it could be an entertaining dive into an entertainment product that rakes in upwards of $580 million a year, forms the basis of an esoteric subset of geek/gamer culture that's probably larger than most people think, and achieved with nothing but colorful pieces of carboard the same degree of slavish patronage which World of Warcraft needed the Unreal Engine and cable internet to inspire in its players.

For people in my age group (read: old) who played for a couple of years in middle school and then wandered off, never to return, it might be a fun way to see how much the game changed over the years.

I should say in advance that I'm not going to be looking at every single Magic set. There's a point where R&D refines its approach to worldbuilding into almost a matter of rote method, and where most of what can be said about a given set is "so-and-so happens in the story," "it's a lot like such-and-such previous set," and "it's inspired by this-and-that real-world culture and folklore." We won't be venturing very far into the post-Mending era.

Since most of these have already been written and need only some touch-ups and pictures, I think I can stand to post them weekly—which might mean I have two months' worth of updates on deck. If I weren't so ashamed of myself for having written so much about Magic: The Gathering, I'd be very pleased.

___________

Today we're going to talk about a pop culture phenomenon that's close to my heart—like some sort of horrible parasitic grub burrowing through my chest cavity.

Magic: The Gathering is the world's first CCG (collectible card game) and is, as such, the originator of the pay-to-play and pay-more-to-win model of tabletop and electronic gaming. It's a great game, wonderfully designed, and the similarities between going up to the counter of a hobby shop and asking for a pack of Kamigawa: Neon Dynasty and going up to the counter at a gas station and asking for a pack of Marlboros are more than superficial. Nobody ever really quits Magic. Once it carves out a space for itself in your brain, you can count on it being a permanent resident. If it ever seems like it's gone, that just means it's sleeping, and it doesn't take much to wake it up again. Spending some time at a place where people are playing Magic, sifting through somebody's collection and examining the new cards, or (god help you) dusting off your old deck and seeing how it holds up are all liable to send you into a downward spiral of consumption and obsession.

I haven't played Magic in over a year. I haven't bought any cards in about three years—if memory serves. But I've been feeling it pecking at the insides my skull again, urging me to take out my EDH decks, or to play some draft games at the ol' hobby shop, or explore the new Pauper format, or...

No. None of this is acceptable to me. It's too much of a commitment. It's too much bandwidth. Definitely too much money.

So instead, I'm going to write a longform thing about Magic to make myself so sick of thinking about it that I'll happily abandon any notion of getting back into it. However much of my time it ultimately eats up will anount nothing compared to the sink of taking the game back up. (Postscript: I may have been mistaken.)

What we'll be doing here is how Magic's approach to storytelling and worldbuilding has evolved since its inception. Yes, there is a story, and it's had thirty years to grow and ramify into a mythos as deep and daunting to the novice as DC/Marvel Comics lore. This isn't going to be too critical an analysis, but if there's a convenient opportunity to talk about the peculiar marriage of culture-industrial pyramid scheme and mythological engine which Magic exemplifies, maybe we'll avail ourselves of it.

For anyone who's not familiar with the game, I'll to try to keep the abstruse technical stuff to a minimum. This will be very image-heavy, but the only stuff you need to pay attention to are the cards' names (at the top left), their color identity (more on that in a sec), the artwork, and the italicized "flavor text" when it appears. Most of the rules text, which indicates how a card behaves in-game, can be safely ignored.

Let's take it from the beginning.

Magic: The Gathering was created by one Richard Garfield, and originally licensed to a small publisher of tabletop games called Wizards of the Coast (which became a subsidiary of Hasbro in 1999). As with most epochal ideas, the concept behind Magic was elegantly simple: take the combat mechanics of a tabletop RPG or computer game and translate them into trading cards.

For instance: instead of glancing at your character sheet and telling the Dungeon Master conducting your Dungeons & Dragons session that you want to cast Magic Missile, you'd simply throw your Magic Missile card onto the table, and what happens next resolves automatically according to the rules of play. Or—instead of going on a quest where you gain experience points, improve your abilities, and acquire new weapons and treasures, you just go out and spend more money on more cards, sold in randomized "booster packs" at your local hobby shop. And instead of sitting down with a game manual and some dice and rolling up character sheet, you'd build a game deck with handpicked cards from your collection. Every so often, new cards would be released, and so you'd have to go out and buy fresh ones to keep up with your friends, who've already bought them, integrated them into their decks and strategies, and can now trounce you and your obsolete build.

It was evil. It was brilliant. And it was a runaway hit. The first cards were released in late 1993, where they caused such a sensation on the West Coast geek/gaming convention circuit that Wizards found itself scrambling to print new cards. (Historical footnote: this was all before Magic achieved national distribution. The early sets were virtually sold out before the game made its way east.)

Enough about that, though: we're talking about narratives here. From the beginning, Magic's fundamental premise was that the player takes the role of a "planeswalker," a powerful (godlike, really), wizard with the ability to cruise from dimension to dimension. The mana-rich world of Dominaria, a hub of plansewalker activity across the multiverse, is the battleground where you and your opponent (another planeswalker) duel for power and control by casting spells, summoning creatures, and so on.

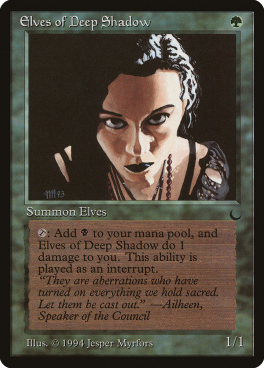

Those five nodes on the backs of the cards (pictured above) represent the five types of magic, each identified by the color of mana that powers its spells. The colors have their distinctive attributes, strengths, and weaknesses. Since color identity eventually comes to tie into the Magic's lore and narrative aspects, let's take a brief look the spectrum:

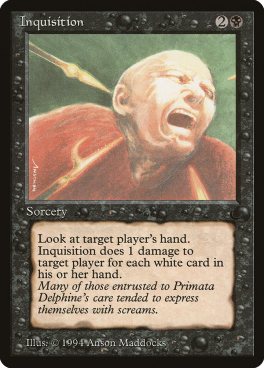

White magic draws its mana from plains. It focuses on healing and protection, and summons critters like knights, angels, and horsies to do its bidding. White doesn't get along with black or red.

Blue magic gets its juice from oceans and islands, and has a bent towards illusion, deception, and mental games. It calls up merfolk, phantasms, wizards, and sea creatures. Blue doesn't like red or green.

Black calls up its mojo from swamps. It's the magic of death, decay, demons, and other evil stuff. Black has beef with white and green.

Red taps into the strength of mountains. To quote the original manual, it's "the magic of earth and of fire, of chaos and of war," and enlists goblins, orcs, dragons, and so on. Red holds a grudge against white and blue.

Green is fueled by forests, and is...well, forest magic. It's about nutriment, growth, and savage destruction, and its signature critters are woodland creatures, fairies, elves, and so on. Green dislikes blue and black.

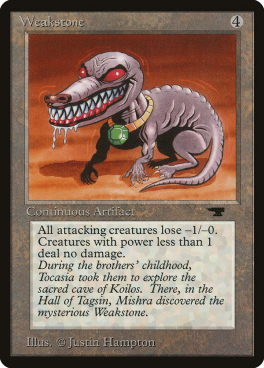

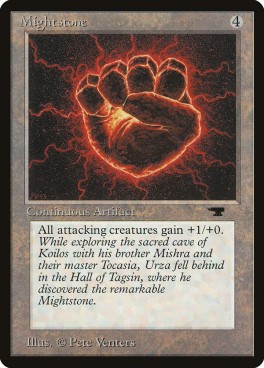

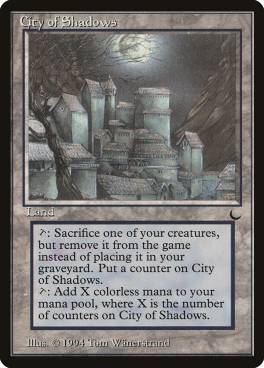

And then there are "colorless" Artifact cards, which represent magical gewgaws.

As you can see, Dominaria began as a pervasively generic swords n' sorcery fantasy setting. Notice how some of the flavor text quotes from Lewis Carroll, Marianne Moore, and Edgar Allen Poe. The excerpts are well-selected, and certainly evocative—but evocative of stuff from Earth, not Dominaria. And...

Wait. Is it "Dominaria" or "Dominia?" Because the text on Demonic Hordes says "Dominia," while the manual says...

Huh. It says nothing. The manual accompanying later editions of the core set definitely calls it "Dominaria," which became a point of confusion among fans. Obviously somebody in an editorial position goofed up somewhere, but Wizards tried to save face by claiming that Dominia is the multiverse, of which Dominaria is just one plane. Much later, Dominia" was quietly changed to "Dominaria" whenever old cards were reprinted.

At any rate: Dominia/Dominaria originated as a template. A pretext. This was to be a game about dueling wizards, after all. The location per se was unimportant, but the sensory and verbal constituents of play had to intersect with and reciprocally reinforce the purely mechanical elements. The artwork does its job well enough; Mark Tedin's illustration for the card Fireball (above) is certainly relevant to how the spell behaves in-game (and vice versa). But the card Llanowar Elves (above) could have simply been called "Elves," and ink saved by not printing a short passage about the customs of any imaginary tribe of elf. Glasses of Urza could have just been called "Glasses," or even "Enchanted Glasses."

It's impossible to know how this would have affected the Magic's debut, but I'd venture to guess that it wouldn't have been such an immediate hit.

A couple of years back, we mulled over the disjunction between the instrumental and sensuous elements in video games, and a similar split exists in a collectible card game like Magic. Theoretically, every illustration and bit of flavor text could be scrubbed from the cards; card names could be replaced by numbers, the pictographic mana symbols by Greek letters, and card types with capital Roman letters; keywords like "flying" and "declare attackers and blockers" could be substituted with a wholly abstract terminology with no material reference; and the system of rules would remain intact, and the game would still be playable. Would it have mushroomed into a global franchise that made billions of dollars in its lifetime and inspired a legion of imitators? Probably not.

What if all the rules text, mana symbols, and every indicator of how the cards function in play were removed, and all that was left were the card names, pictures, and flavor text? How sought-after would these cards be as mere collectibles? Probably not very.

That may be the secret of Magic's success: the gestalt of an elegant, adaptable rules system and a complementary aesthetic—which includes the "literary" adornments and flourishes—that not only gave a narrative dimension to the course of a match, but insinuated the architecture of a larger world in which the cards participated.

If you can't help feeling that this all looks kind of janky and underwhelming, bear in mind that in 1993, nobody had ever seen anything like this before. Magic cards were impressive on the basis that they existed at all. For that matter, nobody had ever made anything like this before. Garfield and friends (heh) were flying by the seats of their pants.

Remember too that tabletop games and "geek culture" in general still occupied a relatively small (and often stigmatized) niche that most adults with disposable incomes weren't interested in exploring. This is to say that Wizards couldn't afford to pay its artists very much, and it's obvious that many of the commissioned illustrators weren't agonizing over the gig. Undoubtedly some of them were just doing it for the sake of their CV and the necessity of not saying no to a paycheck.

But the point is that Magic did very little worldbuilding right out the gate. Adding the descriptor "Serra" to the the angel card (above) marked the angel as something that belonged to Magic's own world, while flavor text (very likely composed after the artwork was submitted), contributed an thin layer of additional meaning to conjoined image of the angel and the flying creature that attacks without tapping. But how does the Serra Angel fit into the order of things on Dominaria? Who knows. Who was the "Mishra" to whom the eponymous ankh (above) belonged? Realistically, nobody—just someone invented to serve as a namesake because a card called "Ankh" would have been a mite humdrum.

But this is all reasonable. Getting the product out there and encouraging people to play was obviously a higher priority than writing out a comprehensive visitor's guide to Dominia/Dominaria (whatever) and squeezing it into 300 or so game cards.

Magic's early success on the West Coast surpassed everyone's expectations. Cards were in high demand, and Wizards scrambled to meet it. In December 1993, four months after the first batch of cards were rolled out, Wizards released Magic's first "expansion set:" a limited run of 92 new cards, sold in separate booster packs from the core set. It was called Arabian Nights, and was based on, well...

There's not much to discuss. Arabian Nights was made because Wizards wanted to print and sell new cards ASAP, and Garfield had been reading Hussain Haddawy's translation of The 1001 Nights. The set oozes with ersatz (but charming) exotic flavor, but doesn't do much worldbuilding or storytelling—and that's what we're looking for here. We can move on.

Side note: in late 1995, when Wizards partnered with Armada Comics (a subsidiary of video game publisher Acclaim) to put out Magic: The Gathering comic books, the first volume was Arabian Nights. The comic carved out a tenuous position for the set in Magic canon by situating it on Rabiah, a plane that's somehow become multiplied into exactly 1001 almost-identical planes. We won't be talking much about the Armada comics—they were a third-party product with a kind of a Schrodinger's Canon thing going on—but what's interesting about Arabian Nights is how its premise seems designed to explain why there can be multiple Aladdin and Sindbad cards on the table during a game. Is it a stretch to imagine that Wizards was getting letters from people demanding an explanation, and asked their new business partner to publish a story that would placate them?

But we digress.

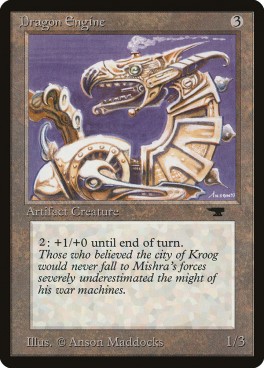

In March 1994, Wizards released Antiquities, Magic's second expansion. Like Arabian Nights, it has a gimmick, but one that goes beyond surficial aesthetics. The set has eighty-five cards, forty-four of which are artifacts, while the colored cards are built to interact with artifacts. While there was nothing stopping the designers from simply dropping these trinkets into the nebulous landscape of Dominaria without regard for any bigger picture, they chose to follow Arabian Nights' precedent by giving Antiquities an identity distinct from the core set. These artifacts, the premise went, were weapons developed during a war that rocked Dominaria in the distant past.

Antiquities was Magic's first concentrated effort at worldbuilding, and it would be interesting to pick the brains of the folks who came up with it. (Reportedly, the creative team actually sat down and drafted a record of battles fought, their locations, outcomes, and so on.) Taken together, the bits of narrative divulged by the cards' flavor text read like a fragmentary historical document discovered on a set of broken tablets at a dig site, implying a much more extensive and involute story that was lost to time.

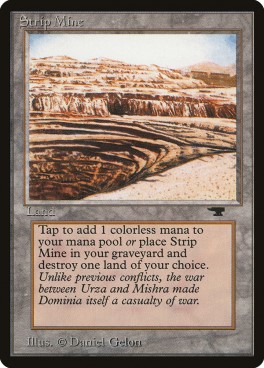

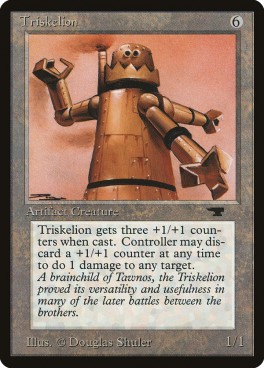

We know that the "Brothers War," as it came to be called, was fought between the artificer siblings Urza and Mishra—names that originated in the first batch of Magic cards (see above), where they were strictly ornamental. We're now told that the brothers apprenticed under the artificer Tocasia, evidently had a falling out, rose to power separately, and subsequently dragged cities and nations into their increasingly destructive feud. A card mentions in passing that Mishra eventually lost the war, but there's no information given as to what brought about his downfall. Whatever became of Urza is anyone's guess, but the cards' silence on that point gives the impression of a pyrrhic victory.

We can't even say who the war's "good guy" was. At the time, most of us assumed it was Urza on the basis that:

1.) His name appears more often than Mishra's, so it seemed natural to think of him as the story's main character—and therefore its hero.

2.) Mishra, we're told, eventually came to despise his teacher Tocasia—so perhaps he was kind of an arrogant and spiteful person?

3.) Urza's second banana was Tawnos, who seems like an upstanding young fellow, given what little information we have. On the other hand, Mishra's lieutenant Ashnod is consistently characterized as a psychopath. "By the company they keep," and all.

With one exception (Hurkyl, below), we don't even know what any of these people looked like. There are no cards called "Urza" or "Mishra" in which either brother is represented. No quotes are attributed to them. It's as though they've simply faded into the mists of history, leaving behind a chronicle of ancient battlefields and a splintered assortment of archeological evidence.

In the core set, each color's respective motely of cards is thematically interrelated, if related at all. White represents no singular realm with such-and-such warrior orders lead by the valiant King So-And-So, red cards aren't unified under the banner of a tribal alliance of orcs and goblins, and so on. Antiquities introduces to Magic the concept of color-based factional identities—an innovation too obvious not to have been adopted before long (maybe the fact that Antiquities has only seven cards of each color prompted the decision by making it so simple to implement), but hardly less consequential in the long term than the set's early efforts at packaging a narrative within a pile of game cards.

Blue is associated with the wizards' school of Lat-Nam...

...Black cards are tied to a plutonian realm called Phyrexia and a demonic entity or force named Yawgmoth...

...Green is about the plight of the Argoth Forest, razed and plundered for its resources by the warring artificers...

...Red has one representative from each of the core set's mountain-dwelling tribes of dwarves, goblins, and orcs, and all of them are overshadowed by the beloved atog...

...And a plurality of white's creatures (two of them) represent a city or nation called Argive.

Notice how the flavor text on Argivian Archeologist is in the present tense. Early on, the artists who contributed card art weren't given detailed instructions. (I recall reading an interview with Melissa Benson, who got an assignment for the original set that allegedly consisted of: "we need a picture of someone in armor." She painted a mean-looking bastard in red and black mail with demonic horns mounted on his helmet, and was salty when it was used for a card named Holy Armor, making everyone involved look silly.) I'm guessing that for Argivian Archeologist, Amy Weber was asked to turn in a picture of an archeologist, so she painted a dude who looks like a modern-day grad student—not a scholar from an ancient era digging up relics from an even more ancient era. (They should have been more specific; the woman's an artist, not a psychic.)

The fix? Write the flavor text to imply that the art isn't supposed to depict a person from the distant past. Easy!

On the topic of art, we ought to mention just one more of Antiquities' innovations: card variants. The core set contained alternate versions of basic lands—but that just made sense. For the uninitiated, basic lands are Magic's resources: every deck needs them, and needs a lot of them. It made sense to break up the visual monotony of eight Island cards sitting on the table by printing three different Islands that were different in appearance but identical in effect.

Antiquities experimented with variants of its nonbasic (special) lands. The most celebrated, I recall, were Kaja and Phil Foglio's illustrations of Mishra's Factory through the seasons. (Only the "autumn" version was ever reprinted after Antiquities came and went; any of the other three was a rare and impressive sight.)

Obviously this whimsical depiction of a ruthless warlord's manufacturing plant is completely at odds with not only the rest of the set's artwork (most of it, anyway), but the tone and tenor of its story. At the time, few people dwelt on the incongruity. In fact, it seemed somehow fitting: recruiting artists with a broad range of sensibilities to visually formulate Dominaria tinctured the inchoate fantasy world with an endearing and apt aspect of plasticity. Later printings of Mishra's Factory, redone with artwork more in line with latter-day Wizards' house style, show a scene that's much more realistic, but also charmlessly banal compared to the original. Ah, well.

If I'm spending an inordinate time dwelling on Antiquities (and I hope to god this isn't a sign of things to come), it's because it constitutes the foundational myth of Magic: The Gathering. Its influence on what follows can't be overstated.

Around 1995–7, when my youthful obsession with Magic was at its strongest, I took a particular interest in the unfamiliar Antiquities cards I came across in people's trade binders and in the glass cases at Hero Town. Remember that this was years before it was possible for somebody go online and view a comprehensive index of scanned cards, lickety-split. Magazines like InQuest contained a complete list of every existing card, their rules text, and approximate value in every issue, but pictures and flavor text were excluded. If you wanted to know the grainy particulars of Magic lore, you had to find it in the wild. I found Antiquities so fascinating because its story comprised a monumental series of events in the Magic universe—and yet it teased more than it revealed about the Brothers' War. There was a mystique here.

But now we (finally) move onto Legends, released in June 1994. A bit of wonky backstory: it was developed as a "stand-alone" expansion, a secondary core set that could be purchased in sixty-card "starter" boxes (containing basic lands and a rulebook) in addition to the smaller booster packs, and was designed to be more beginner-friendly than Arabian Nights or Antiquities. The plan fell through, and Legends ended up being another expansion along the lines of Arabian Nights and Antiquities—but huge. At 310 cards, it was larger than the core set.

A bit more backstory: Legends was designed by some friends of Richard Garfield who had playtested a very early version of Magic in the 1980s, and afterwards amused themselves by jotting down ideas for new cards. Because they had Garfield's ear, because Wizards still had yet to work out an optimal design/release timetable, and because one of these people also happened to be a founder of the company, their casually designed cards were ushered into development.

Legends carried Magic's worldbuilding scheme a step forward by introducing the card type "Summon Legend" (which has since been revised to "Legendary Creature"). Instead of bringing some generic knight, wizard, etc. into battle, these cards are meant to recruit specific persons—many of whom were inspired by characters from Dungeons & Dragons campaigns in which the set's creators participated. This entailed a new rule: only one of any particular legendary creature can be on the table at a time. (This has also been revised, but we'll not get into that.)

The fetishistic stature of the legendary cards is a testament to how much the total aesthetic of Magic infects one's brain. Some were powerful, but the majority of them were fair, middling, or even lousy—and people wanted to use them anyway. The difference between a "Summon Knight/Elves/Dwarf/etc." card and a "Summon Legend" card was akin to the prestige gap between a red shirt and a yellow shirt on Star Trek, or between Wedge Antilles and some nameless rebel pilot in Star Wars. If you were running a white/blue deck, you'd be better off dedicating a slot to one of half a dozen more reliable late-game creatures than to Jedit Ojanen (below)—but none of them were the mightiest of the goddamn Cat Warriors. Finishing off your opponent with a Mahatomati Djinn or Serra Angel just didn't bring the same elan to the table.

The first run of legendary creatures were also the first gold (multicolored) cards. The concept of "enemy" colors already existed, but Legends implicitly introduced "allied" colors. This wasn't exactly a grand design insight; it was as simple as determining that if red (for instance) doesn't like white or blue, then it must have some affinity for black and green. All of Legends' gold cards have allied color identities. This isn't important now, but as the Magic color wheel becomes the basis of a bona fide personality typology, it does become relevant to the lore.

Had the legendary rule existed when Antiquities was being developed, would we have seen Urza, Mishra, Ashnod, et al. represented in cards? I doubt it. As it was, no precedent prevented Antiquities' designers from turning out a "Summon Urza" card the same way Arabian Nights had a "Summon Ali From Cairo" card. The fact that they declined to do suggests that they were taking seriously the body of lore they were developing, and wished for the figures of an ancient war to remain as distant and mysterious as the likes of Gilgamesh and Minos.

Legends also introduced legendary lands and "Enchant World" cards, both intended to represent non-generic places—but these weren't nearly as popular. Every now and again, legendary lands still pop up in new sets, but the world enchantment has been in the freezer for decades. The concept was kind of neat, though: only one enchant world card can be on the table at any time, and it designates the location in which your planeswalkers' duel is taking place, affecting all players simultaneously. (The essential idea was later revived as the basis for the special and very fun Planechase format, but we don't need to get into that here.)

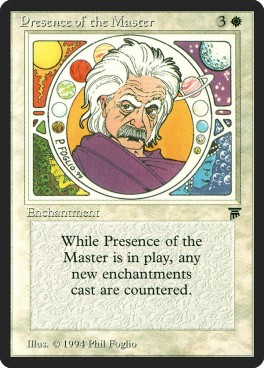

In spite of all this, Legends does little to advance Magic's lore in and of itself. It's a mishmash of proper nouns and fantasy tropes, none of which add up to anything coherent. Some legendary creatures are associated with legendary lands, but that's about as dense as the mythos gets—for now. (A few years down the road, Urborg, Bogarden, Tolaria, etc. will all be substantially fleshed out.) And as you can see above, we're still at a stage where it was perfectly acceptable to have Albert Einstein's mug on a spell card, and when a designer's bookcase could be profitably mined for flavorful and germane quotes to stick to cards whose text boxes needed filling out. Not that I don't like this stuff, mind you. I've a very soft spot in my heart for the days when Wizards was still figuring things out.

Following Legends came The Dark in August 1994. While it eventually got a designated spot in Dominaria's chronology by way of retcon, neither the cards nor any of the marketing material I've ever seen has much to say about the set's context—where or when it's happening, what's happening, etc. The recurring characters in the flavor text (a soldier writing his memoirs, a sinister figure named Mairsil, one Vervamon the Elder, et al.) aren't represented in cards, and they give only us teasingly obscure hints regarding their roles in whatever corner of Dominaria they all occupy. Given the purposive consistency of The Dark's tone, the omission of any reference to a big picture might almost seem like a developmental blunder.

The Dark doesn't have a story so much as a mood, and that's very much intentional. The art and flavor text are powerfully redolent of precarity and anxiety, adumbrating what appears to be an interregnum marked by religious zealotry, a scattered population, a fragile civil order, and desolate, lawless countrysides. On the whole, it feels unsafe (apropos for a set that has a noticeably high number of cards that make their user sacrifice their own assets, or that undermine cards of the same color) and a more cogent story would have detracted from its macabre ambiance by shining a light on its shadows.

Hmm. There's really not much else to say about The Dark. I've a guess to make, though, based on a short story printed in The Duelist (Wizards of the Coast's magazine) to market the new set. Saying nothing about The Dark's setting or story, it instead consists of a short dialogue between two planeswalkers debating the use of "Dark" spells.

"It's not worth it! Brand, there is no way you can control those Dark spells without sacrificing your own life force. It's suicidal!""I told you, I can handle them. I'm not going to use the black spells. I do have some sense of preservation left, you know." Brand smiled wryly.Mindrel shook her head. "You don't understand——it's not just the black spells. All of the spells can turn on you, even the white ones.""I'm not using white either——""I'm telling you it doesn't matter!" Mindrel ticked them off her fingers. "The black ones are indeed vicious, but they're cruel to the caster as well. The unity and defensiveness of the white spells are hideously warped into intolerance and persecution. You can't use blue unless you can deal with your most terrifying nightmares, the ones buried so deep you probably don't even know what they are. And chatoic, uncontrollable red breaks down natural enmities, which can get you into real trouble if you're not careful. Even green is downright brutal, with a vicious backlash."If you've got to lose a duel, I say make the other wizard beat you. Don't do it to yourself by meddling in the Dark."

First of all, let's acknowledge that the official Magic: The Gathering magazine advertised a new product with a story where a character strenuously urges her friend not to use said product. (It was good advice, since The Dark was grievously underpowered compared to the first three expansion sets.)

Also notice that the naysayer's spiel about how Dark spells from all five colors attempts to synopsize the overall vibe of The Dark (even if the descriptions really aren't that accurate) instead of referring to any of the events or places depicted in the set. My hunch is that the designers were still thinking about the game in terms of a tabletop RPG—that the story of Magic existed no more in the cards themselves than did the story of Dungeons and Dragons in the manuals and modules. The real story, they believed, was the one enacted by the players as they slapped cards on the table, pretending they were dueling planeswalkers battling for control of Dominia. Dominaria. Whatever. If the lore became too concrete, it might make the cards the focus of Magic's narrative, when it ought to be the game sessions in which the cards were used.

If I'm right about this, then The Dark was the last set where this assumption prevailed.

NEXT: Cobbling up a Continuity

___________

* The other motivator, I'm sorry to say, was depression. It's been an...unusual winter. This kind of writing is purely masturbatory, and I'm not as proud of it as the stuff that actually requires effort and imagination on my part—but at times when all one wants to do is lie in bed and/or stare at the wall, doing something, even if it's useless, is healthier than doing nothing. I debated whether or not to go through with finishing and posting these, and ultimately decided to go ahead with it on the basis that maybe it could be a valuable diversion for somebody on an evening where it's needed. A small nudge can sometimes make an outsized difference.

As long as I have your attention, let me also say admit I'm not italicizing the names or titles of anything because it's just too onerous and distracting. I feel strange about it, though.

Magic: The Gathering: The Worldbuilding: The Writeup: The Anonymous Comment (1 of a possible 8… not daring to commit at this point).

ReplyDeleteI first want to say, I love your blog. You and I are from the same general era, i.e., the generation that grew up as the internet came into existence and then ubiquity. I find when I read your material, I’m transported through time to whatever era you’re musing about. Not sure if it’s a function of our collective connection to the era or your own writing skills (or if the latter ignites the former, or something like that) but it’s great. Could also maybe be a function of the empty bottle of Jagermeister sitting on my desk…

For someone like myself who tends to do a lot of living in his own head I find your blog to be very therapeutic. I read your blog about your girlfriend, and what happened to her. Seems to me like you lost the love of your life there. Sometimes there are external factors that are like tidal waves of karma and we are powerless against it. I’ve been through a similar situation and understand completely, having been blessed enough to spend 2 years with the other half of my soul until that wave swept us apart.

But on to the post. I never played Magic (I lived in a 700-person super rural town and had very little money at the time) but it’s fascinating to see how this world was built. Or, should I say, your assumptions thereto. I wonder, how much of this world is really just reactionary scrambling to give players something to hold on to and was never really given much deep thought by the creators? I remember hearing something about Akira Kurosawa once. He was asked why he chose to frame a particular shot in the way he did, and he said something akin to “well, if I had moved the camera 3 feet to the left, you’d have seen the Toyota factory in the background”. When it comes down to it there are so many pragmatic and practical reasons why creators make the choices they do and we, as consumers of their creations, tend to overestimate the amount of precognitive creation that goes into making a product like Magic (or a movie, or videogame, etc.) and underestimate how much or it was simply based on a business decision, or some forced outside factor. Looking forward to reading your next installment… which I see you have now posted.

I always was more of a Yu-Gi-Oh fan myself but I give Magic credit for being around even longer and yet still mostly keeping things from getting out of hand...mostly...well at least compared to the mess Yu-Gi-Oh is now in.

ReplyDeleteIt's especially funny about Yu-Gi-Oh when you consider how it started as a manga with a very very different story.

DeleteAll to true...his entire story was morphed to keep the success of the one Card chapter going...and its STILL going today...however degraded the Rush Duels are.

DeleteI argue that the three-way marriage between mechanics, fantasy art, and implicit world-building lore was not so much a serendipitous confluence as a canny marketing ploy by Garfield who understood the audience the potential audience for his intricate moving-parts competitive puzzle and the pop-cultural trappings that would capture their attention.

ReplyDeleteIn other words: Nerds coming off the formative 80s were known to play D&D and read novels with Boris Vallejo illustrations on the cover; so if you made a game for nerds, you better make it feel and look like that.

I'm really enjoying these write-ups. I've read through the first 4 parts last week. I wanted to comment on each one as I went along, but the preview function annihilated my first comment, so that didn't happen.

ReplyDeleteI just wanted to say that I really appreciate you writing these. What you said in the asterix is true, and your words have helped occupy my mind and imagination during a difficult time. So, thank you.