So, yeah: Kaervek and his beasties are running amok in Jamuraa. Jolrael realizes that helping him was a bad choice, and rescinds her allegiance. A posse of heroes embarks on a mission to rescue Mangara, but one of them dies in the process. Teferi comes back. Kaervek is defeated. The end!

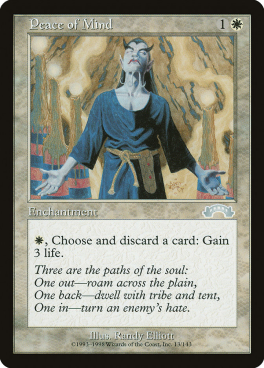

Delivering a narrative through a collectible card game sold in randomized boxes and packs containing cards of varying rarity presents obvious challenges. For instance: it wasn't until many years after Visions' release that I saw the card Natural Order (above) and learned that Asmira died. I did own a copy or two of Relic Ward (above), but wasn't aware that there was another card out there that completed the sentence begun in its flavor text. No player is guaranteed to physically encounter every card that constitutes the main nodes of the plot; and if those nodes are sufficiently dispersed, it can be difficult to arrange them in the intended temporal sequence.

The effectiveness of Mirage and Visions' delivery is further hampered by the dissonance between the flavor text and the art. Notice how Natural Order depicts a cheetah, while the flavor text reveals Asmira's demise. We could point to several other examples above. My guess is that the designers weren't really thinking about it. Until now, they never had to set aside certain cards to represent key moments in a plot, and maybe it didn't even occur to them that these cards might need to be specially considered: "okay, we need to convey that Jolrael switches sides, so let's earmark a card to name 'Bitter Abnegation' and write a memo telling the artist to draw Jolrael fleeing Kaervek's camp under cover of darkness, etc."

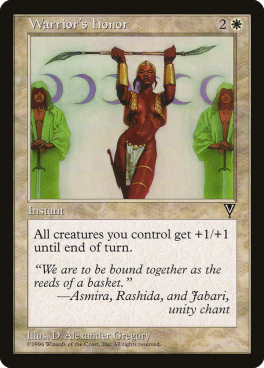

Naturally, all the heroes are white-aligned, and Kaervek's friends and monstrous allies are all black. Because white is good and black is evil—obviously. (We'll return to this.)

The "Love Song of Night and Day" is actually a full poem written by Jenny Scott, a (former?) Wizards employee as a world-building exercise. Reading isolated verses at the bottom of thematically-related cards is like peering into Jamuraa's cultural psyche; I always had the impression of a song that was a touchstone of an old oral tradition and later fixed in writing. It truly does come across as verses translated into English from another language, losing the rhyme and meter of the original but retaining the foreign idioms. (I recall reading translations of Sanskrit poetry in which the comparison of a woman's gait to an elephant's was intended as an elegant compliment, and would have been read as such in situ.)

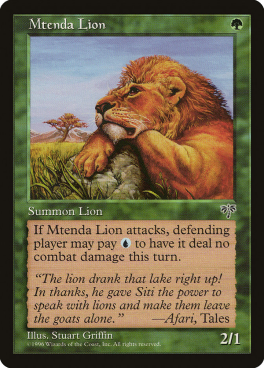

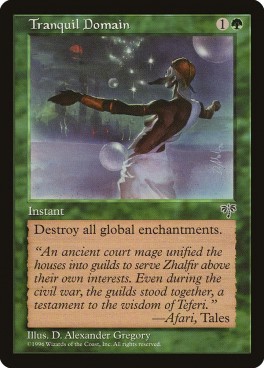

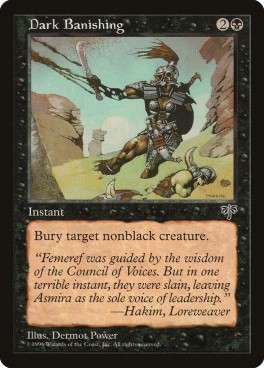

Mirage delivers some its most evocative worldbuilding through this and other such excerpts from folktales, proverbs, colloquialisms, and other aspects of Jamuraan culture, undoubtedly devised to imitate residual orality. Afari, to whom the Tales are attributed, strikes me as a compiler of orally transmitted fables and folklore who was subsequently regarded as their sole author. The Loreweaver Hakim seems to have a little bit of both Herodotus and Thucydides in him, collecting myths and observing history as he travels Jamuraa. There are excerpts from a fablist named Azeworai, Zhalfirin and Femeref songs and riddles, the Poetics of one Hanan, and so on. This isn't the only time Magic invented a fictional tradition of literature and folklore to serve as a worldbuilding instrument, but no other set used it to the same extent as Mirage/Visions, or did it with such gusto.

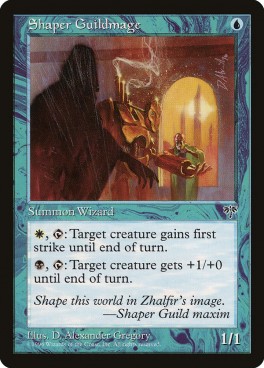

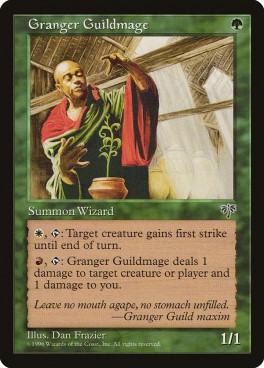

A very minor but far more inventive worldbuilding trick Mirage toys with has to do with using the color identity of certain cards to tell us something important about Zhalfir, the largest and most powerful of Jamuraa's three (human) nations. Each color is given a "guildmage" card, representing an order of wizards in service to the Zhalfirin state. You can see the red one (Armorer Guildmage) up above; the rest are below.

Here the functional and narrative aspects of Magic combine to characterize Zhalfir as an enlightened, cosmopolitan kingdom. Even the black-aligned guild makes a civic-minded contribution to the national welfare. What's more, the guildmages do nothing for players running monocolor decks: their abilities need a second and third color to activate. Diversity literally makes them stronger.

One final thing I'd like to point out is more evidence of synergy between Wizards and third-party publisher Armada. The two-issue Arabian Nights comic, based on the Magic expansion whose inbuilt lore amounted to "here's some cards inspired by famous Middle Eastern folktales," situated those cards on a plane called Rabiah. In Mirage, there's a card that namedrops Rabiah—along with, uh, King Suleiman of the Koran (aka King Solomon of the Bible), who appeared as a card in Arabian Nights.

Wizards has since then been very transparent about its intention to never, ever, ever revisit Rabiah.

Interesting that Mirage would give a nod to the Arabian Nights comic, since Wizards had recently broken things off with Armada, as well as with HarperPrism (publisher of a line of Magic: The Gathering novels). There'd be a four-issue miniseries by Dark Horse comics in 1998, but from then on, Wizards was finished with third-party publishers. It began to...

...Huh. Wait. Time out for a second.

What was that one black card up there called? "Phyrexian Tribute?"

That's interesting. Mirage's move to Jamuraa meant that Magic's story finally stepped outside the centuries-long shadow cast by the Brothers' War. Of the six expansion sets released between Antiquities and Mirage, four were about the conflict's long-term aftermath. Jamuraa, on the other hand, was completely uninvolved in the artificers' feud and unaffected by the worst of its fallout. (Magical climate control. Oh, if only.)

What I mean is that there's no good reason for any Antiquities-era leftovers to be down here.

Huh. Imagine that.

What this demonstrates, if anything, is the multifariousness of these imaginary worlds we glimpse through Magic's cardboard windows. Selecting only only a couple dozen out of the five hundred cards comprising Mirage and Visions doesn't give nearly the complete picture. There's a whole lot of stuff we've left out: the Viashino clans that rule the deserts, the goblins and dwarves of the mountains, the Suq'Ata military and its draconian leader Tellim'Tor, the pirates of the Kukemssa Sea, the order of assassins called the Breathstealers, and so on. I can't speak for anyone else, but Magic had me as hooked on the richness of its lore as on the dopamine taps of acquisition, competition, and pseudo-RPG mechanics.

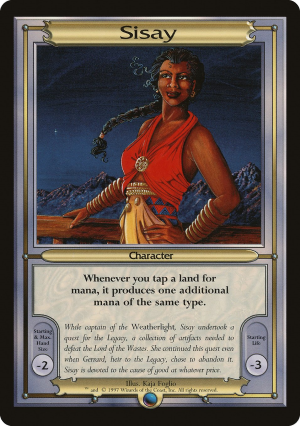

One other minor facet of Mirage and Visions' scenario was the peripatetic life of Sisay, captain of the airship skyship Weatherlight—the namesake of the set that followed Visions, and the one that weaned me off Magic for fifteen years.

Nominally, Weatherlight (June 1997) is Mirage's second expansion, but it's actually more like is an episode of a TV show that functions as the pilot of a spin-off series. We haven't completely left Jamuraa, but the scope has expanded to include Urborg, Yavimaya, Benalia, Tolaria, and Keld—Dominarian regions that have either previously appeared or been mentioned in earlier sets. Mirage and Visions, as it happens, were also the first sets taking place in modern-day Dominaria, which until now we've only seen in the core set.

So...here's the thing about Weatherlight. Remember how we said that collectible card games aren't an ideal medium for character-based, plot-driven storytelling? Well, this is where Magic's creative department abruptly went full steam ahead with character-based, plot-driven storytelling. It was a mess.

I'm not sure where I read it—probably somewhere on

Multiverse in Review, but I can't find it now—but it seems the

original plan was to put out a few more sets that continued to emphasize worldbuilding over storytelling, where Sisay and the Weatherlight (and possibly other crew members?) kept appearing in the background. Only after players had some time to get acquainted with these recurring characters would Magic's story zoom in on them. But somebody made the decision to eliminate the timetable and swerve precipitously in the new creative direction.

I've sifted through the indices on Scryfall and tried to pick out fourteen cards that might function as a rough storyboard, sketching the trajectory of Weatherlight's plot. Take a look and see how much sense it makes to you:

How'd you do? Honestly, I'm not even sure if these are in the right order.

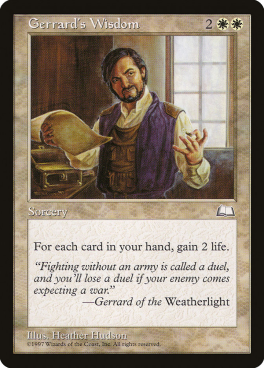

Let me see if I can synopsize this thing without consulting any plot summaries. Captain Sisay travels the world in her flying ship, collecting the artifacts of The Legacy in order to put down the Lord of the Wastes. Sisay gets kidnapped, presumably by the Lord of the Wastes. Her old friend Gerrard takes command of the Weatherlight and flies around recruiting crew members. Then they have to contend with the

Keldon warlord Maraxus for some reason. Some guy named Starke stabs Maraxus in the back, and Gerrard takes him into the crew.

Uh...the end.

Weatherlight's marketing literature made a lot out of the switch from worldbuilding to storytelling, implying that now, for the first time, the 167 cards of the new set could be arranged such that they'd delineate the progress of a band of heroes on their way from Point A to Point B. That, uh, certainly wasn't my experience.

Scroll back up and look at the text for Thran Forge. If you were reading those closely, you may have suspected me of withholding information. You'd think that there'd be at least one other card showing the situation that compelled Gerrard to "use the Thran Forge to strengthen the Aboroth", and at least one other card depicting the outcome of this apparently desperate gambit. You'd be wrong.

You might also think that Thran Forge should depict the eponymous artifact being used on the creature we see in the card Aboroth (above), or that the card Abjure (above), whose flavor text narrates a moment where Ertai brags about how awesome he is, should actually depict Ertai instead of some random wizard. I'm not sure why none of this crossed the minds of Weatherlight's designers.

Opening Weatherlight booster packs was the first time I felt I understood a Magic set's lore less as I saw more of its cards. But the mistake was mine: I picked the wrong months to neglect picking up The Duelist (the official Wizards of the Coast magazine), which not only provided exposition, but published short stories written by Magic's senior editor that elaborate on the various events glimpsed at in the cards. So it's not so much that Weatherlight's cards are telling a story, but illustrating one that the player has to go elsewhere (and buy a copy of Wizards' magazine) to read.

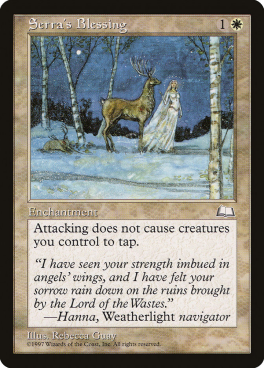

This material in The Duelist contains a great deal of new information. For instance: Gerrard takes the Weatherlight to Tolaria, where he recruits the navigator/gadgeteer Hanna and the wizard Ertai. Hanna's father Barrin is an instructor at the Tolarian Academy, and he sends his student Ertai with Gerrard because he's got too much on his plate to go on a rescue mission. None of this is mentioned in the flavor text. Crovax grieves for his parents, who were murdered by the monsters Morinfen and Gallowbraid—both of which are represented as legendary creature cards, but their roles in upending Crovax's life are left unspecified. Mirri is supposed to be one of Gerrard's oldest and dearest friends, though you wouldn't have guessed it from looking at the cards.

Weatherlight doesn't just readjust the balance between storytelling and worldbuilding; it virtually eliminates worldbuilding. Here and there we find cards whose flavor text conforms to the conventions observed up until now: a pithy statement by some omniscient narrator, a quote from a fictional text, or a remark from a character that's appropriate to the illustration, etc. But the purpose of Weatherlight's flavor text isn't to flesh out the setting, but to flesh out the cast.

Hmm. We might as well meet them, since we're going to be spending a lot of time with them.

Real fast:

Sisay: Intrepid, upstanding skyship captain. Damsel in distress.

Gerrard: Protagonist. Headstrong man of action. Heir to The Legacy.

Mirri: Temperamental catgirl.

Tahngarth: Minotaur meathead.

Ertai: Conceited young wizard.

Hanna: Artificer/girl next door.

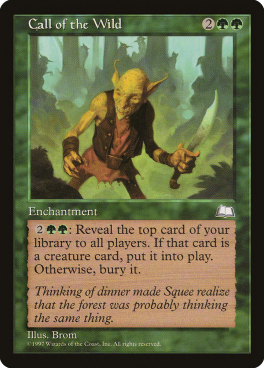

Squee: Dopey comic-relief goblin.

Crovax: Gloomy sadsack.

Karn: Golem sadsack.

Orim: Doesn't exist yet because she's not mentioned until the next set.

Starke: Career liar and traitor.

There you have it. Their chattering in Weatherlight takes up all the air in the room, and it's hard to get emotionally invested in them when all you're given is a jumble of dissociated moments from their journey sold in randomized booster packs. Some of them we don't even see: nowhere in Weatherlight are Ertai, Hanna, or Karn depicted. You wouldn't have any idea what they looked like unless you read The Duelist, or invested a few bucks in Vanguard.

Concomitant with the pivot towards a continuous, character-driven storytelling in Weatherlight, Wizards released eight oversized cards sold in two packs of four, representing important members of the cast: Sisay, Gerrard, Ertai, Karn, Tahngarth, Crovax, Squee, and Maraxus. The Vanguard cards give the definitive images of these characters and the essentials of their backstories, but they're also a component of an alternate play format. Each player chooses a Vanguard card, which sits on the table the entire game, changing their starting life total and maximum hand size, and generating a potentially powerful effect that persists through the entire game.

I have nothing nice to say about Vanguard. I hated it so goddamn much. The Arena League allowed participating locations to set their own rules, and Hero Town made Vanguard mandatory during the season when Weatherlight was rotated in. It distorted play and spawned some absolutely busted decks that nothing could be done about.

Knowing that Gerrard and his crew of pop fantasy stereotypes would be Magic's narrative focus for the foreseeable future was disheartening enough, but it was Vanguard that pushed me over the edge. I quit Arena mid-season and stopped buying booster packs. Most of my friends who'd played Magic had already quit by then; the one who hadn't was kind of a prick and I didn't like hanging out with him anyway.

So that was it. Final Fantasy VII, Tool, Marilyn Manson, and writing stories about a team of superheroes who got their powers from pounding Jolt Cola became my new preoccupations. I was done with Magic. (Or so I believed.)

But the story continues. From here on out, I'm looking at these from some distance. Since I only became acquainted with the following sets much later on, I'll probably have less to say about them. Maybe things will speed up a bit...?

Tempest (October 1997) was Magic's third stand-alone set, and evidently the last to be marketed as such. By then people had adjusted to the "one big set, two little sets" release template that began with Ice Age, and remained in place for nearly two decades.

Ice Age, the first stand-alone expansion, had the "ice world" gimmick. Mirage, the second stand-alone expansion, went antipodal with a tropical setting. If this was a Mario game, I believe the next iteration in the series would have to be either "water world" or "pipe world." But since this isn't a Mario game, Wizards was permitted to skip right to the "dark world" locale.

I remember the previews for Tempest describing Rath as a "world of evil," though it really comes off more as a world of austerity and desolation. Storm clouds perpetually shroud the sky, the landscape is either barren or rank with jagged trees and deep-water swamps, and the sentient races that aren't aggressively persecuted by the tyrannical Evincar Volrath are feral, nasty, and/or collectively insane. Even the white critters in Tempest cards aren't quite as benevolent and cuddly as we're accustomed to seeing them.

So: after the business with Maraxus and Starke, Gerrard has the Weatherlight planeshift to Rath—and if you did your homework and read the Weatherlight stories in The Duelist, you'd know how it is that Gerrard knew to go looking for Sisay in another dimension. This is the first time a "big set" has had a chance to explore a plane other than Dominaria, and Tempest's premise offers ample space for the wide-view worldbuilding of sets like Mirage and Ice Age. Or at least it would, if that was still how Magic was doing things. Now the setting is just the ambiance in which the character-centered action plays out.

Let's take a look at the "storyboard:"

That's enough. If I don't stop now, I'll keep slipping in more. There's a lot we're skipping, and I didn't even get to the end.

The good news: by being much more thorough than Weatherlight, Tempest succeeds where its precursor failed in packaging a linear narrative (with subplots and branching arcs!) into a set of collectible cards. Granted, one would have had to shell out for a lot of booster packs to do it, but Tempest's cards can be arranged into a more or less coherent story.

The bad news: remember how I complained about story-relevant cards not depicting the characters whose actions are referred to in the flavor text? I take it back. I'm certain that if I'd bought a box of Tempest boosters, I'd have gotten real sick of looking at Gerrard and friends. Problem is, this is precisely the basis of the good news.

The ugly news: there doesn't seem much point in analyzing how Magic tells stories now that it's become so straightforward: buy the cards, find the ones with the main characters or the flying ship in the pictures (or their names in the flavor text), and put them in order like a sequential jigsaw puzzle. Easy peasy.

The Tempest block uses a new kind of format to tell an old kind of story in an old kind of way. It's basically an action-fantasy comic where the reader collects the disarranged panels (and the "Flash Facts" filler pages) in fifteen-card booster packs. It's decent enough, but the older sets were a lot more interesting because they played to the strengths of the format.

You know: I did buy a couple Tempest boosters, purely out of habit. None of their contents ever saw any play, and as far as I know they're still in a box at my folks' place. Some of the cards mentioned Volrath, painting him unambiguously as Tempest's big bad, and I kind of assumed he was the Lord of the Wastes. Had I kept reading the magazines or invested in the next edition of Vanguard, I would have learned that he's just a high-ranking lackey. I suppose that's just as well; it would have been a letdown for everyone if the big, mysterious, almighty evil Lord of the Wastes looked like one of Jabba the Hutt's palace servants.

You know the one I'm talking about.

One of the cards I got in those booster packs was Phyrexian Hulk. By that point, there'd already been Phyrexian stuff floating around the margins of four consecutive expansion sets, so I don't remember being much puzzled by its appearance in a fifth.

Interesting that Robot Hell swag would have found its way to another dimension, though. But Volrath seems like a collector and a tinkerer, and Phyrexia matches his style. It makes sense. I don't think anyone read too much into it.

Stronghold (March 1998) picks up where Tempest left off, and is more of the same. Gerrard and friends sneak into Volrath's gargantuan citadel while the elves and en-Vec tribes stage a frontal assault.

Huh. We needn't give much in the way of an introduction, since Stronghold picks up exactly where Tempest left off, and stays the course in terms of how it uses the format to tell its story.

Let's just skim some of the storyboard, I guess.

As before, there's a whole lot we're leaving out, but these are the important points: Rath is apparently preparing to invade Dominaria. Karn and Tahngarth are sprung from captivity. Gerrard fights Volrath, but it turns out to be a shapeshifting decoy. Crovax kills

Selenia and gets slammed with a curse, turning into a vampire—and becoming the first of the OG Weatherlight crew to be represented in a legendary creature card. (Orim and Starke were legendary creatures in Tempest, but we saw neither hide nor hair of Orim before then, and nobody cares about Starke.)

Hmm. Until now, I assumed the designers gave Crovax his card in Stronghold in anticipation of him going AWOL for a while. Most members of the "team" don't become playable until the moment where the story prevents them from appearing any later. Mirri and Ertai, for instance, each get their legendary cards in the next set, where one of them gets killed off and the other gets left behind.

But that's not it: the people who'd devised Weatherlight's story thus far were shunted into different roles after Stronghold, and the writers who took over in the next set promptly implemented some rewrites.

Turns out, Crovax's heel-turn (see below) wasn't in the original script. The idea was that the Weatherlight's black crew member (as in, the one representing black mana) ought to be a vampire, but that posed the question: why would the good guys have an undead bloodsucker on their team? Well— what if he joined the quest as a human, and became a vampire later on?

That probably accounts for why this interval was chosen to debut Crovax the Cursed: events in the story have made him who he's meant to be. (Not that anyone asked, but I very much prefer angsty goodguy Crovax over the wantonly homicidal meatlord version we'll be meeting later.)

Hmm. You know who hasn't been mentioned at all in a while? Volrath's boss, the Lord of the Wastes. The patchwork exposition in Weatherlight told us that Gerrard and Sisay are both sworn to safeguard The Legacy and use it to defeat the Lord of the Wastes, who's apparently very evil and dangerous—but that's still all we know about the saga's big bad. Do you suppose Volrath is...

...Hey, wait. Time out again. Scroll back up. What's that say in the flavor text of Stronghold Taskmaster?

Yawgmoth? Wasn't he that demon or whatever associated with Phyrexia? Had a couple of cards in Antiquities named after him and was never spoken of again?

Well, the name doesn't appear anywhere else in Stronghold. Maybe it's some kind of easter egg for longtime players or something? It's probably nothing.

Anyway, it's time to close this out with a glance at Exodus (June 1998), the third and final chapter of the Tempest block.

I mentioned earlier that the people in charge of the Weatherlight Saga's story were reassigned to other design roles, and Exodus is where the plot deviates from its planned course. Apparently I wasn't the only person disappointed by Magic's swerve from macro-lore into micro-plotting, because Exodus quietly puts the engine in reverse.

To somebody paying close attention in 1998, the backpedaling would have been apparent. In Stronghold, I count thirty-seven "story" cards that either picture the main characters, indicate places they visit on their way through Volrath's fortress, or depict pivotal moments in the plot. This was just a rough count; maybe I would have tallied a few more if I took a closer look or relaxed the criteria for "story" cards. In Exodus, I count eighteen—a reduction by more than half. (Both sets have 143 cards.)

So much for that experiment, then. (It will be back much later, in modified form.) Speaking of wrapping things up, we might as well see how Tempest block's plot resolves and then call it a day.

Once again, I'm not certain these are in the correct order. Having fewer "story" cards means they're more dispersed, and it can be tough to discern their context.

But it's all straightforward: with Sisay rescued and the Legacy artifacts recovered, it's time for the Weatherlight and its crew to get the hell out of Dodge. The now-vampiric Crovax goes berserk and kills Mirri. Gerrard fights Greven, and succeeds in getting him off everyone's backs. The Weatherlight races to the portal out of Rath, and speeds through before it closes (leaving Ertai behind). Urza watches on from a distance.

Wait—what?!

Well...with all this lore I'm shocked that Magic never had a TV show like Yu Gi Oh and the others. I( Glances at the news) Ah...not sure if your getting to this but just wondering if you have any thoughts on Magic: The Gathering's long-awaited animated Netflix series coming out in the second half of 2022, with Superman Returns star Brandon Routh revealed to be taking the role of lead planes walker Gideon Jura? Good? Bad? Fated to be canceled after a week when it does not get Squid Game's views? ( RIP Cowboy Bebop's netflix show.)

ReplyDeleteOooh, thanks for the official response. I played Blasphemous but I glazed over the lore, like the philistine that I am. It helps that the devs barely had to invent anything: all they had to do was recontextualize weird stuff Christians are doing or have done, like capirotes, parading the dead, “holy” self-mutilation and being really into collecting bones.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, be careful what you wish for? So Magic cards had a “real” story... and it was dime-novel stuff about a swashbuckling sky pirate and his “wacky” crew? I like the bit about the Love Song of Night and Day though. I think that’s the sweet spot for flavor text: pithy statements about the subtly different way fictional people view the world... with as few Capitalized Nouns as possible.

I’m catching up on the last 15 years of Magic with this. Whatever will happen next?