We're drawing closer to the point where I started playing Magic: The Gathering again after Weatherlight alienated me, and something occurred to me regarding Magic's remarkable persistence as a game, a community, and institution.

Somebody who collected and played with Magic cards at any point in their lives can return to the game after a decade or longer and still use their old cards at kitchen table games. If their collection consists mostly of cards from Mercadian Masques and Invasion, they probably won't win many games today—but their old decks still qualify them to participate in casual play with friends. The metagame changes, sure, but the only cards that have become completely incompatible with the game are a few very old ones that assumed people played for ante.

Once again, let's use Street Fighter as a counterexample. A person who dropped hundreds of quarters playing Street Fighter II circa 1993, skipped out on Street Fighter Alpha, Street Fighter III, Capcom Vs. SNK, SNK Vs. Capcom, etc., and then had his interest piqued by Street Fighter IV in 2008 would have discovered a game that resembled the one he'd been hooked on a decade and a half earlier, but was nevertheless a different animal. Street Fighter IV's Ryu might handle similarly to his Street Fighter II version, but even apart from the all the new moves, IV's fundamental mechanics are not the same as II's. Even if all the hours he committed to playing Street Fighter II gave our guy a leg up on somebody who was a total novice to 2D fighters, he still had to learn an entirely new game with its own intricacies and fine technical points.

Magic: The Gathering is like what Street Fighter II would be if Capcom had continuously updated it with new characters and the occasional balance tweaks for thirty years. (If "Super Street Fighter II Turbo" is a cumbersome title, imagine what its twentieth or thirtieth version would have been called. By that point, Capcom would have probably taken a cue from SNK and called it Super Street Fighter II Turbo 2021 instead of something like Double-Plus Ultra Street Fighter II #Reloaded Champion βst ¡Prime! Edition." But we digress.)

I suppose Maple Story is a good instance of a video game actually doing this in practice. Hundreds of thousands of people still play Maple Story, but that's a precipitous decline from the 92 million users crowding its servers back in 2009. It's clearly showing its age, and there's the dilemma: at this point, modernizing it would amount to melting it down and remaking it. Nexon might as well just announce Maple Story 3 at that point—and judging from the brief lifespan of Maple Story 2, its reluctance is understandable. Since its obvious datedness precludes it from attracting many new players, the plan seems to be to let it run on fumes for as long as enough people still play it out of habit, come back for the updates, or revisit it in a sudden fit of nostalgia (as Shirley did last winter), and are enticed to spend real money on fake swag once they're there.

But playing cards don't obsolesce. They're slips of cardboard. A CCG has no user interface that becomes clunky in comparison to newer products, no core engine that hits its practical limit, and relatively few "patches" (rules changes) that fundamentally change how cards operate in play. Thirty years later, your Beta Edition copy of Lightning Bolt still deals three damage to any target at instant speed, and nobody cares that the art isn't digitally enhanced, the card layout differs from later printings, or that the wording of the rules text isn't as rigorous as it became later on.

If you knew how to play Magic twenty years ago, you know how to play it now. Adjusting to things like the removal of mana burn from the rules and the loosening of the restrictions on legendary creatures (the same player can't have two copies of Jedit Ojanen in play, but two different players can each have one) might take some getting used to, but you're not going to be like the inveterate Street Fighter III fanatic (me) who tried to like Street Fighter IV, but couldn't get past the idea that it was an inferior reiteration.

There was never a Magic: The Gathering II, Magic: The Gathering Champion Edition, Magic: The Gathering Sword & Shield. After almost thirty years, it's still the same game—which goes a long way towards accounting for how easy it can be to get hooked on it again after a long absence. The original recipe and all its addictive active ingredients remain exactly the same.

___________

While Magic's modern era officially begins with Mirrodin, I feel that the turning point from old to new was just after Time Spiral. This is the skewed perspective of a lore fiend who wasn't playing the game in the 2000s, so perhaps I know not of what I speak. But hear me out anyway.

We didn't say much about the Time Spiral novels last time, but they culminated with an event called The Mending—the dividing line in Magic's chronology. The long and short of it: the time rifts on Dominaria were closed and the plane's mana channels were restored, but for some reason (because it's a lot of pop fantasy mumbo-jumbo), the nature of the multiverse and planeswalkers were forever altered. Planeswalkers ceased to be veritably immortal, omnipotent godlings. Now they aged at the rate of any member of their species, and were much easier to kill—no more of that "Urza got disemboweled and willed himself whole again" stuff that was all over the novels. They could no longer create their own worlds like Serra and Karn did, bring people with them when they traveled between planes, and didn't level up straight to 99 when their spark activated. Now they were just people (or lion-people, dragons, vampires, or whatever), usually with inborn magical talents, who could warp between planes after their "spark" was activated.

Why was this important? We'll get into that shortly.

Anyway, here we are in the post-Time Spiral sets, and we're once again looking forward instead of backward. Before we go on, it's worth mentioning the triplicate block problem, and Time Spiral's solution to it.

Ever since the Mirage/Visions/Weatherlight triad became the template of Magic releases (one big set, two small expansions, released roughly five months apart), the challenge has ever been to keep people engaged with an aesthetic and mechanical status quo lasting the better part of a year. For all its failings, the Masques block was the first that seemed to have acknowledged the issue, and was designed to dodge it. (Perhaps because the some of the negative feedback Wizards of the Coast received about the Urza block touched on how it amounted to ten months of the same vibe, the same characters, the same mechanics, and more or less the same setting.) Each of the Masques block's three sets are situated on a different plane and feature different characters, and the two small sets introduce mechanics exclusive to themselves (Fading in Nemesis, the rhystic gibberish in Prophecy). Kamigawa, Mirrodin, and Ravnica differed little between their individual sets in terms of their flavor; unless you were reading the books or looking very closely at a few pieces of flavor text, there was little indication that a story might be unfolding. The idea was that new mechanics introduced in the second and third sets would be sufficient to keep things interesting, even after ten months of "well here we are in the Japanese/artifact/city plane." For hardcore players, it was probably enough—though the introduction of the last three guilds in Dissension was undoubtedly more exciting than the debut of the sunburst ability in Fifth Dawn.

But maybe somebody still felt that extra steps ought to be taken to prevent players' ten-month stay on any one plane from becoming monotonous. Time Spiral achieved this by playing with alternate universes in its second set and future timelines in its third. The sets following it took a different approach: introducing a new setting, and following a period of upheaval through three(ish) acts. Sort of like what the Onslaught block did—though Onslaught didn't have a well-defined setting, and the changes wrought upon Otaria were somewhat hard to follow.

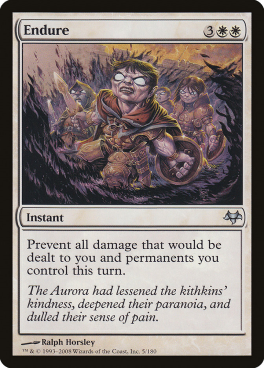

First, let's take a look at the ambitious and perhaps underappreciated Lorywn block. As a side note, this is where Future Sight retroactively got real, as a couple of its "futureshifted" cards were reprinted here. ("How many more will follow?" was the obvious question.)

Inspired by the folklore of the British Isles, Lorwyn (October 2007) and Morningtide (February 2008) present a world that's markedly more whimsical than Magic players were accustomed. Lorwyn is a place where the sun never sets and it's always midsummer, and whose sentient races are more prone to the occasional border skirmish than the ruinous wars we're used to seeing in Magic stories.

Lorwyn came about a decade after I quit playing Magic and about five years before I picked it up again after being introduced to the EDH format, so I can't say anything about how much fun or how miserable it made the metagame—but from a distance, I'm a little surprised by reports of its lukewarm reception. On the face of it, it's neither soporifically weak or stupendously overpowered, and it's full of tribal themes, which a lot of people appreciate. (Though

apparently the emphasis on tribal mechanics made for dauntingly complex board states.)

And the setting! The aesthetic! Lorwyn is a pastoral plane of off-brand hobbits called Kithkin, mischievous faeries, boggart pranksters who love their Auntie, wise giants, and elegant card names like "Squeaking Pie Sneak," "Peppersmoke," "Hurly Burly," "Glimmerdust Nap," "Noggin Whack," and...

...Yeah, okay. I think I understand why Magic's predominately 18–34-year-old male player base didn't vibe with Lorwyn.

At any rate: humans are out, hobbits halflings kithkin are in. Lorywn has no oceans, but its merrows (merfolk) traverse its sinuous rivers, making them their world's merchants and couriers. The faeries and goblins can be dangerous, but both seem more interested in playing pranks and having a good time than wreaking havoc. And there are wise giants, vivacious elemental "flamekin," derpy changelings, beneficent treefolk...and asshole elves. Lorwyn's elves are its only truly nasty group: a pack of narcissists obsessed with eradicating ugliness, which boils down to "everyone who's not an elf."

Yes, Lorywn certainly seems like it would be one of the Multiverse's most pleasant places to visit—provided one stopped in at the right time.

The big structural innovation of the Lorwyn block was its division into four sets: two big ones, two small ones. Lorwyn and Morningtide were the first big/small pair. Shadowmoor (May 2008) and Eventide (July 2008) were the second.

Like the protagonist of Fight Club, the plane of Lorwyn leads a double life. During the day, it's a bucolic storytime world—and daytime lasts 300 years. When the clock ticks down, an event called the Great Aurora precipitates its 300-year transformation into Shadowmoor, a desolate and deadly nightmare world shrouded in perennial twilight. And as far as its vicious inhabitants are aware, their world has always been Shadowmoor.

The only tribes that don't come out worse for it are the elves and faeries. The elves' purpose in life changes from exterminating the ugly to protecting the beautiful, and the faeries—they're exactly the same as before. How mysterious!

One could read the books if he or she truly craved an explanation, but Lorwyn/Shadowmoor are perfectly complete coherent on their own: we become acquainted with life in a bucolic, Shire-like fairyland, and then dive into its transformation into American McGee's Hobbiton. It's not really deep, but awfully charming, even when it's dark and creepy.

Also, there's planeswalkers.

Sometime around 2007–8 (I think), my friend Dave briefly got back into Magic, and asked me if I wanted to play. So I dug up my old cards, blew the dust off, reassembled my old Necropotence and all-Mirage flanking decks, and sat down across the kitchen table from Dave. The only thing I remember from any of the games we played that day was him dropping Liliana Vess on the table and me asking "what the fuck is that?"

Planeswalker cards! To the understanding of the mid-1990s Magic player, such a thing ought to be impossible. The players of the game are the planeswalkers; how can there be planeswalker cards? It didn't make any sense.

Dave patiently (if a little smugly) explained how they work. Loyalty counters—okay, sure, planeswalkers don't have life points, but a discrete quantity indicating how much more work they're willing to put in for you. Makes sense. Actions like spells and creature attacks that ordinarily target the player can be aimed at the planeswalker instead, pissing them off and prompting them to leave? God damn it—it all checked out.

Personally, I was happier playing Magic in a world without planeswalker cards, where Karn Liberated and Jace, the Mind Sculptor never ruined my shit—but I can't say they were ill-conceived. Moreover, they represented a compromise where Magic's card-based lore and supplementary story materials could coexist without interfering with each other. Players could understand new scenarios and feel out the world just by collecting and gawking at the cards, while certain events, teased in the cards, would be explored through in-house publications.

Moreover, the Time Spiral books forced a tightened chronology going forward. Remember, planeswalkers aren't immortal anymore. They age. If planeswalkers were going to be integral to the lore going forward, there could no longer be centuries-long gaps between sets.

And they were going to be integral to the lore. Their introduction in Lorwyn augured a rebranding program that would make planeswalker characters the faces of Magic: The Gathering. It couldn't happen all at once: Wizards still remembered the backlash it received after the Weatherlight crew became Magic's main characters no sooner than they were introduced. The original plan had been to incrementally introduce Gerrard & Friends before positioning them front and center, and it seems Wizards now saw the wisdom in the approach not taken.

This also explains why it was necessary to depower planeswalkers and reduce them to mere morals. Serra lived for thousands of years, created her own world, and was literally enthroned at the top of an angelic host. It's hard to relate to somebody like that. It's difficult to even call her a nice person, since "person" isn't the first word I'd choose for somebody whose body is the corporeal avatar of her immortal will, and has seen and done enough during a long and effectively unlimited lifespan to accept the title of "goddess" when it's been offered. The new breed of planeswalker was going to be somewhat more like the Avengers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe: powerful, attractive, sympathetic, between twenty-something and thirty-something years old (or otherwise looking and acting like people in that age range), and as down-to-earth as dimension-surfing wizards can conceivably be.

The new planeswalkers' creep into the lore was gradual. None of the five planeswalkers introduced in Lorwyn are mentioned in the block's flavor text, appear in any other illustrations, or enter into the novels. It would be another year before any new planeswalkers cards were released; apparently Wizards wanted to give players some time to get adjusted to the new concept and card mechanics. It may seem odd that the new planeswalker's first appearance should be so understated, but it does follow the logic of what planeswalkers are supposed to do. If Chandra was on the plane, she was only sightseeing, or maybe chatting with the Flamekin. For all we know, Jace stopped by to take a leak on his way to an appointment on some other world. Each of them was present, but uninvolved. But now they were there, and that was the point. (Fun postscript: it seems planeswalker cards were intended to debut in Future Sight—which would have been much more appropriate—but needed a bit more fine-tuning before going live.)

In October 2007 (the same month of Lorwyn's release) Wizards debuted Chandra's Ultimate, a one-shot online comic about Chandra Nalaar. In 2008, it was followed by webcomics featuring Garruk Wildspeaker, Liliana Vess, Jace Berelen, Sarkhan Vol, and Tezzeret (the last two of whom were introduced in Alara). In 2009, Wizards put out more planeswalker webcomics, along with two planeswalker novels and single novel for the Alara block (which starred Ajani Goldmane, one of the Lorwyn planeswalkers, and Elspeth Tiral, who was introduced in Shards of Alara).

Again: slow and steady. Nobody had to know what any planeswalkers were doing in order to appreciate the lore presented in the cards—although the explanations for "how did this big world-changing event happen?" were usually detailed in the books or webcomics, and almost always involved planeswalkers. Still, the designers made it easy to get a handle on what was happening in the big picture, and the planeswalkers' presence in the cards was restricted to in-game representation (although "planeswalker" was and remains the rarest card type), one or two quotes in the flavor text, and the occasional cameo appearance in the illustrations. It was a far cry from the oversaturation people complained about during the Tempest block.

Meanwhile, Wizards was, ahem, diversifying its Magic line with new products such as the From the Vault series. The first of them, From the Vault: Dragons (August 2008), reprinted and bundled fifteen classic cards, packaged with a special life counter gewgaw, all for the low, low price of $34.99! ($46.98 today, according to an inflation calculator.)

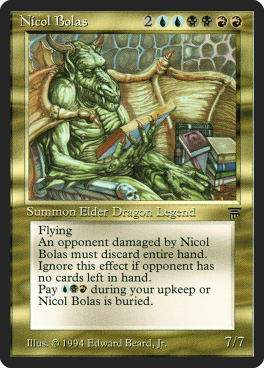

What, do you need another selling point before you hand over your money? Well, what if I told you that some of the older cards have new art? Yes, illustrations that no longer conform to Magic's house style have been duly consigned to history and replaced with art that looks like all the other art! Fuck you, Amy Weber! Fuck you, Dana Knutson! Fuck you, Sam Wood! Fuck you, Melissa Benson—I mean, we already had Donato Giancola replace your

iconic Shivan Dragon art back in Seventh Edition, so fuck you

and Donato!

And fuck you too, Edward Beard, Jr.!

Hmm. You know—I'm half-convinced that From the Vault: Dragons was a neat (and lucrative) pretext for a visual retcon of Nicol Bolas. Wizards had already blown its chance once: Bolas was reissued with his old art in Time Spiral, one of 121 old cards that were reprinted and given a slot in the booster packs. And he needed to be updated, since the "smirking dragon chillin' with his favorite books" image didn't comport with his appearance in the Legends Cycle and Time Spiral novels, where he's depicted as a malevolent, Smaug-sized saurian tyrant.

And his earlier incarnation needed to be brought up to speed (sort of like an edited photograph of party officials in Stalin's Russia) because, like Urza before him, the elder dragon legend was about to come back in a big way.

Fun fact: I've been inserting images into these posts by copying the high-resolution versions from Scryfall, resizing them to 264 by 368 pixels in Paint 3D, copying the reduced images, and then uploading them to Blogger from the clipboard. Something bizarre happened when I uploaded the two images above: having just uploaded Nicol Bolas, Planeswalker, I copied Conflux from Scryfall, opened Paint 3D, and hit ctrl + v. But nothing happened.

I tried it again. Highlighted Conflux, hit ctrl + c, moved to Paint 3D, hit ctrl + v. Nothing.

I closed out of Paint 3D and started it up again. I hit ctrl + v—and the pasted image was of Nicol Bolas, Planeswalker.

I highlighted a random card image from Scryfall by dragging the cursor across it, right clicked, selected "copy" from the drop-down box, opened the Blogger tab, and tried to upload a new image from the clipboard. The image that got uploaded was Nicol Bolas, Planeswalker.

I can't explain it. For whatever reason, Bolas refused to vacate the clipboard. I would have regarded it only as an inconvenient fluke if it weren't so perfectly, frightfully in character for Bolas. (I'm a little sad we won't be covering Bolas'

villainous debutante ball in

Hour of Devastation.)

Returning to the subject of publications: a month before releasing Shards of Alara (October 2008), Wizards published the 160-page Planeswalker's Guide to Alara: a primer on the new set's locale, full of concept art and lore. And if there was ever a set that warranted the purchase of a $16.96 field guide ($22.77 in 2022) it was Alara.

We're at a point in the evolution of Magic design where there are a lot of concepts and content that never make it out of the artists' style guide or other internal documents, but that are nevertheless canon as far as the people working on a set are concerned. Alara's central conceit ensured that more ideas than usual would fail to make the journey from the design document and concept art into the cards.

Mechanically, Alara was a spiritual sequel to Ravnica, but one that encouraged players to run three-color decks instead of two. Instead of ten two-color factions, Alara has five factions of allied triples: white with blue and green, black with blue and red, etc. The scenario conceived to complement the gimmick was a plane separated into five "shards" centuries ago. What once was a single world is now five isolated mini-worlds, and the passage of time has seen them evolve in drastically different directions.

Hence the need for a field guide. As we've seen in our glance at Mercadian Masques, constructing and relaying the feel and flavor of a world through some hundreds of cards is probably easier to screw up than most of us would suspect. Shards of Alara tries to flesh out five worlds simultaneously, and has just 249 cards to do it. (For the record, Mercadian Masques had 350 cards.)

To the designers' credit, it's easy enough to infer what plane a single- or double-colored card depicts (a green card could represent an entity or event on one of three planes, while a green and white card could possibly depict a scene from either of two), but watermarks might have been helpful to keep the affiliations straight, or to emphasize them. As we'll see, the direction of the Alara block would have prompted burdensome design choices that the creative team was probably happy not to have sweat over.

Each of the five shards is missing two of the five colors of mana, and I'd guess that figuring out the landscape and culture of each of Alara's planar islets consisted of asking what would happen if the remaining three colors operated without any interference from the missing two. Like the Ravnican Guilds, it's a matter of following the logic of each color's "philosophy." For instance: the white-dominant Bant is missing black and red, so it's a place without ruthless ambition, reckless passion, chaotic violence, insidious scheming, zombies, dragons, etc. So it's basically a happy sunshiny place where angels visit from the skies, everyone works together, selflessness and order are prized, and where political disagreements that escalate to the point of no return are settled by honorable duels instead of open war.

It would be tedious to review all five shards in detail—you can always just check the wiki. But, in short:

Bant: White/blue/green. Martin Prince's home planet. Has the exclusive "exalted" mechanic, which gives a bonus to a creature when it rides out to battle by itself.

Grixis: Black/blue/red. It does the mash. It does the monster mash. Probably the only place in the multiverse to make Phyrexia look pleasant. Some Grixis critters have the "unearth" ability, which lets you spring them from the graveyard for one last party.

Jund: Red/black/green. Volcanoes, dragons, savagery. Features the "devour" ability, which lets you make a critter bigger when it hits the table by feeding it some of your other critters.

Naya: Green/white/red. Jungle world. No special keywords; just big critters.

Esper: Blue/white/black. We'll be zooming in on Esper, since it's by far the most interesting of the shards, and probably the most enduringly popular. It doesn't have any special keywords either, but it's got artifacts. Lots of artifacts. Colored artifacts!

I'll be honest: I hate Esper. Artifact-heavy control decks are the bane of my existence in EDH, and Esper's colors are an ideal vehicle for them. (When I got back into the game a few years ago and visited a card shop to play with random people, I had a one-on-one session with a guy running an Esper deck. I forget who his commander was. When he had me all but locked down and unable to act, he'd spend his turns fiddling with triggers, tapping and untapping things, replacing the cards in his hand with the top cards of his library, and so on, for at least five minutes. All I wanted in the world was for him to find a way to kill me so I could get on with my life.)

Nevertheless, Esper is a cool concept: an artifact-themed world that manages to have an identity completely distinct from Mirrodin. Esper, strong in blue mana and devoid of green and red mana, is a place that prizes knowledge, artifice, ambition, and order, where passions run cold and the natural forces are tame as a tired housecat. The rulers of Esper are sphynxes, and vedalken seem to be just below them in the world's racial hierarchy. A magical metal called etherium is a mark of power and prestige; the people of Esper replace their organic parts with the filigree alloy, enhancing their physical and magical capabilities, and prolonging their lifespans.

In Conflux (Feburary 2009), the shards begin to reconverge. Swaths of land on each plane (along with every person, plant, or monster that happens to be on them) are dropped onto the four others overnight. The second chapter of the Alara block is about the people of each world recoiling from unfamiliar lifeforms and making cautious and/or belligerent incursions into strange new lands.

Also, Nicol Bolas is there, and he's trying to harvest the energy from the maelstrom of planar convergence to get his pre-mending planeswalker powers back. (Read the book.)

In Alara Reborn (April 2009), the violent and traumatic incursions of the five shards into one another have ceased, and they once again form a complete world. If mass migrations of people lead to unrest and violence on Planet Earth, imagine the chaos that ensues when the populations of five different continents simultaneously resettle on each other's territory, and bring everything with them. Alara may be whole again, but it'll probably be a while before it arrives at any sort of equilibrium.

Vedalken Heretic is my spirit animal, by the way. Yes, I'm a Simic. All the dumbass online personality tests say so. The Ravnican guilds are Myers-Briggs for irredeemable nerds.

To represent the merging of the plane as a set mechanic, there are no monocolored cards in Alara Reborn, and abilities that were once exclusive to a single shard have become democratized: Grixis demons have Bant's exalted ability, Naya's artifacts are colored like Esper's, Jund beasts have Grixis' unearth ability, and so and so forth. If watermarks à la Ravnica were ever being considered, Alara Reborn would have either meant doing away with them for the finale, or coming up with at least ten new ones representing combinations of the original five. It would have been a huge pain in the ass, and I can appreciate why the designers didn't go there.

Like Lorywn, the following block flouted the "one big set, two small set" release model. It's one of the most popular blocks, and

maybe one of the most controversial. And as an exercise in worldbuilding, it's pretty darn decent.

Zendikar (October 2009) began with a "lands" theme. Why not? Mirrodin had an artifacts theme, Lorwyn had a tribal theme, Ravnica and Alara had multicolor themes—why not lands? That hadn't been done before!

The plan didn't pan out. Zendikar might have slightly more nonbasic lands than usual. It introduces the "landfall" mechanic, which generates an effect whenever you drop a land. The block's second set, Worldwake (February 2010) introduces the "manlands," which produce allied-color mana and turn into creatures that can run over and deck opponents who take their eye off them for too long. But overall, Zendikar's land theme ends up being as half-realized as the enchantments theme intended for the Urza block.

I'd guess Zendikar's aesthetic elements were conceived when the plan was still to design a "lands world," similar to how Mirrodin was Planet of the Artifacts. I'm speculating here, but this was probably where the concept of the Roil was floated. Zendikar is a world whose surface is always changing. When the Roil sweeps across the landscape, forests abruptly become mountain ranges, prairies become oceans, and not in a poof! kind of way. Geological events that would ordinarily take millennia play out in a matter of hours, with all the violence that entails.

I'd also surmise that after the Roil was locked in and the creative team was brainstorming about the kinds of cultures Zendikar supported, somebody proposed: "let's make it like Indiana Jones, but crank it up to twelve. Not eleven—twelve."

Zendikar is all about treasure hunters and ancient ruins. Jungles and treacherous mountain passes. Wild animals and hostile natives. Traps and hazardous terrain. It's a lot of fun.

Just as Otaria's economy seemed to revolve around arena combat, Zendikar's is apparently based on tomb raiding. Cities don't last long on Zendikar—but at some point in its history they did—and they're full of highly sought-after goodies, and expedition houses (based in the persistently stable parts of the world) run a booming business matching ambitious treasure hunters with survivalists, navigators, bodyguards, and the like.

Supposing that Zendikar's basic premise followed from the original plan of a "lands" set, it was the "expedition into the wilds" conceit that ultimately informed most of its mechanics (though I'm

I'm told that landfall, the vestige of the "lands world" idea, ended up dominating the the competitive scene anyway.) The "quest" cards—enchantments that do nothing at first, but produce a powerful effect once certain conditions have been met—are the in-game narrative equivalent of reaping the rewards of completing a side quest in an RPG. (Because, you know, the "main quest" in a game of Magic is to beat your opponent, but having a card like

Beastmaster Ascension on the board gives you the ancillary objective of attacking with seven creatures to gain a power boost! Side quest! Overanalysis!) The creature type "Ally" emphasizes the survival benefits of venturing out into the wilds with companions: the more Allies you have on the board, the more potent each of them becomes. Traps are designed to act like switches that a player unwittingly trips as they go about their turn, and they can

feel like it.

Even superficially, there's a lot of cool stuff in Zendikar. Jungle-dwelling vampires, for instance, aren't something you see too often in either horror or fantasy pop culture. The kor, introduced as subjugated race on Rath way back in Tempest, actually originated in Zendikar, where their entire way of life seems to be built around mountain climbing. Unless I'm mistaken, Zendikar also gives Magic its now-standard take on merfolk as amphibious bipeds.

It might just be me, but I feel that Zendikar and Worldwake toss around more mysterious proper nouns than is usual for a new Magic setting. Most of them are the names of places, and they contribute to the impression that Zendikar is a big and largely unknown place, even to many of its residents. Maps, after all, don't mean much when the world's geography is as temporary as its weather.

Oh...and there's planeswalkers, too.

Their slow and steady creep into the lore continues. Even though Bolas was at the epicenter of the chaos in Alara, we didn't see that much of him in the cards. We met a couple new planewalkers on Alara too (Sarkhan Vol and Tezzeret), but neither of them showed up often, either.

Planeswalkers might have slightly more of a presence on Zendikar (and I emphasize "might"), and if we're reading the webcomics that have started appearing on Wizards of the Coast's website, and maybe made a point of reading The Purifying Fire novel (which introduced Gideon Jura before his in-game debut in Zendikar's third block), we probably have a better idea of what they're doing there. For the most part, the planeswalkers are simply a few more voices in the chorus, and a very occasional source of foreshadowing. We don't need to pay attention to them if we don't want to.

Chandra and Jace get new cards in Zendikar and Worldwake, respectively. The first set introduces Sorin Markov and Nissa Revane (pictured in Groundswell, above), while Sarkhan Vol...

Hmm. Wait. What was that Jace was saying? Eldrazi? Didn't those cards up at the top of the section say something about them, too?

It's funny: Zendikar retells the Steamflogger Boss joke from Future Sight, except this time it's being serious.

When players opened Zendikar booster packs and found the mythic rare artifact Eldrazi Monument (above), most of them were more interested in its potential applications than its lore. Again, Zendikar drops a heaping bundle of proper nouns into players' laps, and for the most part there's little indication that any of them are more significant than any other, since there isn't much of an overarching story beyond "grab your gear, we're going on a dangerous expedition to [insert place here]!" How about to the heart of Khalni, for instance? Where and what is Khalni, you ask? I dunno—it's a forest, apparently! Khalni Gem's flavor text refers to an ancient place(?) called Ora Ondar, but that name doesn't appear anywhere else. So...who knows!

Point is, there was no reason for anybody to suspect that "Eldrazi" was anything other than what "Urza" was in the original core set: just a cool-sounding name invented to gussy up a card that might otherwise be called "Ancient Monument."

Four months later, the same person who'd gotten an Eldrazi Monument in a Zendikar booster pack opened his first Worldwake pack and found an Eye of Ugin (above), whose text partially reads: "Colorless Eldrazi spells you cast cost [two colorless mana] less to cast." But there were no Eldrazi spells to cast.

Even though Eye of Ugin's flavor text is suitably ominous, Steamflogger Boss' "Whip the Xs! Pinch the Os! What we're building, no one knows!" might have actually been more appropriate. Unlike the Steamflogger Boss and his contraptions, nobody doubted that Eldrazi were on the horizon, and it was anyone's guess what they were.

Returning to the topic of proper nouns for a moment...

In addition to bombarding us with strange place names, Zendikar also hits us with the appelations of several local deities. This should be familiar to anyone who's spent even a reasonable amount of time squinting at italicized text on these cards. Since the early days of Magic, when worldbuilding was done ad hoc, the creative team often invented the names of a few deities to give the culture of a giving setting a little bit more depth (or the illusion of it). The druids of Argoth worshipped Titania, and the elves of Yavimaya worship Gaea. In Fallen Empires, the merfolk of Vodalia revered Svyelun, while the nation of Icatia and the Order of the Ebon Hand deified the figures of Leitbur and Tourach, respectively. The Kjeldorans of the Ice Age block worshipped Kjeld. Tahngarth of the Weatherlight invoked the name of the minotaur god Torahn. The aven of Otaria exalted the Ancestor, Bant venerated the memory of the angel Asha—and so on.

Every now and again, these gods ended up being planeswalkers (Serra, Leshrac, Freyalise, et al.), and played roles of considerable importance in the lore. Except in very rare cases (Ravnica's Rakdos and Alara's Progenitus come to mind), they tended not to be represented in cards. Most of the time, their presence was only felt to the extent that their names popped up in the flavor text.

The good news for Zendikar's faithful is that they get to meet Cosi, Ula, and Emeria in Rise of the Eldrazi (April 2010). The bad news...

Which is the more horrifying revelation: that the benevolent empyrean deities you and your ancestors have worshipped for centuries are actually distorted memories of eldritch titans from the void between worlds—or that the movie you're in isn't Indiana Jones, but Cloverfield?

You can learn more about how it happens if you read the book (singular) and the webcomics, but a group of meddling planeswalkers unwittingly release a trio of long-slumbering Lovecraftian horrors from their primordial tombs, and they commence to flooding the world with their horrible spawn and causing an awful ruckus. Once again, the details aren't that important to gawking at the horror. All you need to know is that the Eldrazi are loose, and Zendikar is in mortal peril.

To anyone who's literate in Magic mechanics, just looking at the Eldrazi titan's legendary cards communicates the planetary magnitude of their threat. They're some of the last creatures you want to be looking at from across the table. For one thing, they're huge. In a standard twenty-life game, two hits from any of them is game over, even for a player who hasn't so much as been nicked yet. In addition to everything else they do, Kozilek and Ulamog's annihilator ability forces you to toss out four of your cards in play whenever they attack, and that's before you decide whether to shove a meatshield between them and you. And all that you need to know about Emrakul is that she's banned in EDH. In a format where it's actually fairly likely that somebody will be able to pony up the mana or employ some shenanigans to cast her, she's simply too powerful for fair play.

An excellent intersection of flavor and mechanics: if you manage to kill one of the titans, make your opponent discard one, or otherwise put it in the graveyard, it doing so just causes your opponent to shuffle it and all the rest of his used cards back into his draw pile. The implication is that the Eldrazi can't be destroyed—only put back to sleep.

Even the nonlegendary Eldrazi are repulsively large, and many of them have a weaker version of their sires' annihilator ability. The saving grace is that they all have steep casting costs—but that doesn't help much, since cards like Eye of Ugin make them cheaper to bring out, and smaller Eldrazi critters create spawn tokens that can be squished for a shot of colorless mana.

Way back in the days of the Weatherlight saga, Magic committed a variation of "telling, not showing" sin with regard to figures like Crovax, Gerrard, and even the Phyrexians. Crovax was built up as a vampiric Attila the Hun, a ruthless, insatiable conqueror—but as a legendary creature, he was a milquetoast. The Phyrexians invading Dominaria were treated as an implacable existential menace to Dominaria, but their in-game representatives were often somewhat underwhelming. Rise of the Eldrazi does not have this problem. If the majority the non-Eldrazi cards were still about treasure hunts, I'd call it a design failure.

This was why the designers made the unorthodox choice of making the block's third set a large expansion. Rise of the Eldrazi tosses all the themes and mechanics of the first two Zendikar sets out the window and introduces new ones. Traps, landfall, allies, and quests are out, and their replacements needed ample room to be developed as much as they needed to be. In terms of the intersection of mechanics with lore, there's not much point in treasure hunting at a time like this. This isn't like a JRPG, where our heroes have all the time in the world to go on a few sidequests before armageddon comes crashing down.

But Rise of the Eldrazi is like a JRPG in that you can level your guys up and make them stronger.

Zendikar's fate is still up in the air at this point, but the fact that its defenders are apparently getting stronger and better at fighting the Eldrazi as time passes suggests that the doom of their world isn't a foregone conclusion.

I'm sure it was hard not to be enthralled by the sudden turn in Zendikar's story, but a lot of people weren't happy that the third set in the block got rid of all the things they most liked about the block's first two sets—and depending on who you ask, their replacements may have left something to be desired. (Killing a Goldfish makes the opposite claim

here.) For one thing, the Eldrazi's signature annihilator ability is so powerful and so

not fun to be on the receiving end of that when Zendikar was revisited later on and the Eldrazi plot resolved, annihilator went unused. And the level-up mechanic, while neat on paper, had a mixed reception in practice. It didn't come back in either of Magic's returns to Zendikar.

It's strange: the concept of the Eldrazi as a part of the lore ended up being really popular with fans, but I've played EDH games with more than one group who had a "no Eldrazi" house rule. Hmm. Is this the CCG analog to the JRPG fan's assessment of the game that's a chore to play through, but has a good story?

Eventide continues a trend of "Hasbro wanted WotC to release a summer set when the core set cycle was in the off-year". Finally rectified with the release of M10 and the yearly core set release.

ReplyDeleteAfter you demystified Coldsnap, I figured it was something like that. Certainly was a better way of making lemonade out of lemons than "let's pretend to make a third Ice Age set," though.

Delete