In some ways the Critique of the Power of Judgement resists synopsis. The Critique of Pure Reason and Critique of Practical Reason each possesses a linear structure wherein an elaborate argument is built up from its foundations and followed to the pinnacle of its conclusion, whether Kant intends to construct and justify a bounded but flexible epistemological system (the first critique) or to provide an annex in which that system can house a moral objectivism, assert the logical and practical necessity of doing so, and explore what that entails (the second critique). The third critique, on the other hand, often seems tangential to itself.

Let's say Kant has a greater and a lesser ambition for the Critique of the Power of Judgment. On a more modest level, Kant wants only to examine the faculty of judgement in and of itself, and see if it contains an a priori guiding principle like the other two "higher" cognitive faculties (the understanding and reason). If that's the case, he pins that principle (the perception of purposiveness) down in the Introduction, and having established it as conclusively settled, proceeds to spend the next three hundred pages ruminating on its ramifications, with detours into matters of fine art and biology. Any outline of the procedure would be as scattershot as the book itself, and academic wonks have noticed that Kant doesn't actually ground many of his remarks on beauty and organic forms upon the intricacies of our judging faculty. (See here, sixth paragraph.)

More daringly, Kant also purposes to span the divide between the remote continents of natural and moral philosophy. That's a hell of a hook (especially if you're already familiar with the organization of the Kantian system), and it had me eagerly turning the pages as soon as Kant alluded to the possibility in the Introduction. Imagine my surprise when our dear philosopher presently embarked on a deep dive into judgements of taste and art.

Not that this stuff is altogether irrelevant to Kant's stated purpose, and not that it wasn't tremendously influential in its time—it cannot be emphasized enough that the Critique of the Power of Judgement inaugurated the definitional shift of the word "aesthetic" toward its modern usage—but it's possible to finish the Introduction, skip the Critique of Aesthetic Judgement altogether, and begin reading the Critique of Teleological Judgement and not find your understanding of it much impaired. We simply can't do this with the Critique of Pure Reason: if the first-time reader leapt ahead to the Transcendental Dialectic after reaching the end of the Transcendental Aesthetic, he'd find himself hopelessly lost.

Giving an overview of the Critique of the Power of Judgement with regard to its more grandiose intention without setting aside whole swaths of the book as extraneous is a daunting prospect. People who've made careers for themselves reading and writing about Kant have evidently taxed themselves trying to discern an internal consistency within the text as a whole. As an amateur, I find myself at something of a loss.

I feel that the most sensible and expedient way of writing about the third critique would be to look separately at its aesthetic and teleological sections, paying attention to the areas where the concerns of the first and second critiques overlap. I should say again, for anyone who's actually reading this, that I'm writing this as a summary for my own benefit (internalizing the text by compelling myself to parse and restate parts of it), during which I'll pretend that I'm explaining to a curious roommate what I've been reading lately.

|

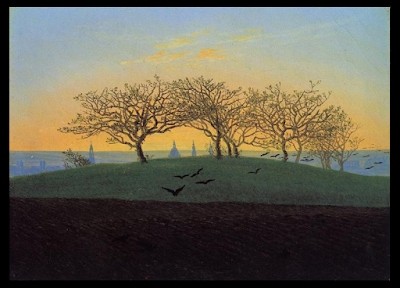

| Caspar David Friedrich, Hills and Ploughed Field Near Dresden (1825) |

Let's get the basics of Kant's definition of beauty and the beautiful out of the way.

The experience of beauty is of course, a source of pleasure. Kant ranks the sorts of pleasure in ascending order from most to least pathological: the agreeable, the beautiful, the sublime, and the good. For now it'll be enough to explain the first and the last items on the list. Something that's agreeable merely pleases the senses or gives us some sort of practical (or technical) advantage. Money is agreeable. Sex is agreeable. Playing chess is agreeable. Writing a blog post about Kant is agreeable (if you're having fun with it.) As per the Critique of Practical Reason, the agreeable stands in contradistinction to the good, which is intertwined with and defined by moral duty.

He arranges his exposition of the beautiful and of judgements of taste (the act perceiving beauty) in terms of the four "titles" or "moments" of logical judgements he identified back in the Critique of Pure Reason: quality, quantity, relation, and modality.

Concerning quality:

Taste is the faculty for judging an object or a kind of representation through a satisfaction or dissatisfaction without any interest. The object of such a satisfaction is called the beautiful.

We can take this to mean that the pleasure we take in the beautiful is of a different sort than what we experience when we cash a paycheck, prevail in an argument, win in a game of chess, solve a problem, and so on. We can also understand the pleasure of beauty as one that has nothing to do with either sensual gratification or the satisfaction of fulfilling a moral obligation. In a sense, it's a free pleasure, enlivening us independently of the flesh's inclinations, reason's dictates, or mechanical associationism.

Concerning quantity:

That is beautiful which pleases universally without a concept.

This gives us two points to unpack. Kant believes there's no pathway from concepts per se to pleasure (except where the pure practical, or moral, laws of the second critique are concerned, and that's a special case), so the experience of beauty can't be grounded in any concept given to us by the understanding. At the same time, beauty has a universal validity, though that universality is subjective. I don't think it's necessary here to get into the weeds of Kant's wonky deductions, but we should mention the example he gives from common experience: we typically speak of beauty as an attribute of an object, when it reality it's a relation between the object and the perceiving subject (person). Kant agrees with the adage that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, though he insists that every human beholder looks upon it with a standardized set of eyes. When we regard something as beautiful and say so, we're miffed when somebody disagrees with us. We expect, even demand consensus where judgements of taste are concerned.

What we're talking about when we talk about the beautiful is a state of mind. That state of mind, for the record, consists of the "free play" of our faculties of imagination and understanding, and the pleasure which results. Let's just leave it at that.

Concerning relation:

Beauty is the form of the purposiveness of an object, insofar as it is perceived in it without the representation of an end.

As the commentators have noticed, Kant arrives at this conclusion without once bringing up the reflective mode of judgement, which featured so prominently in the Introduction. Again, we won't dwell on Kant's justification of the claim (we've got a bit of ground to cover), but we should bear in mind the distinction he makes between aesthetic and teleological judgements. The latter does involve the representation of an end, while an aesthetic judgement (or one of taste) only requires formal or subjective purposiveness—for instance, the purposiveness we perceive in a symphony, which neither gratifies us sensually, advances our material interests, nor explicitly intersects with the concerns of pure practical reason.

On the topic of music: Kant maintains that beauty has nothing to do with emotion. In the case of music, we can only discern beauty in the aural structure of an orchestral performance, not the way it excites us. I'm not sure how many of us would agree with him—though he does tell us in advance that there's an emotional component in the experience of the sublime, which we'll get into shortly.

Concerning modality:

That is beautiful which is cognized without a concept as the object of a necessary satisfaction.

In some ways this recurs to Kant's remarks on the moment of quantity in the judgement of taste. He posits a common sense (sensus communis), based on the communicability of feelings. In other words, the fact that we can talk about mental states and be understood implies not only that each of us experiences beauty in the same way, but that each of us necessarily finds beauty in the same objects—or should, if we perceive them clearly.

This is important: Kant is a man of his time in that he doesn't think of taste as a matter of personal preference. In response to the question "is this beautiful?", Kant believes there is a right and a wrong answer on a priori grounds. To cultivate one's taste is to improve one's ability to recognize beauty when he sees it, and to distinguish it from what's simply charming, shiny, arousing, etc.

Kant occasionally returns the importance of sensus communis to our understanding of taste; later on he'll offer an alternate definition of taste as "the faculty for judging that which makes our feelings in a given representation universally communicable without the meaning of a concept." (Since this is Kant, "representation" doesn't refer to a painting of something, but to an object of experience.)

There. That was a very, very basic account of Kant's main ideas about beauty. Here's hoping I didn't leave out anything important or mess something up.

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, The Dreamer (1840) |

Let's remind ourselves what we're after here.

Philosophy, Kant tells us, is split into two streams: theoretical/natural and practical/moral. The rock that splits them is found in the epistemology set forth in the Critique of Pure Reason. All of our knowledge of nature is is knowledge of mechanistic phenomena, not of things-in-themselves, while pure practical reason, presupposing both free will and an objective moral duty, relies on ideas of the noumenal (or supersensible) world beyond the play of appearances given to us by our perceptual faculties.

But the supersensible law of freedom must be able to achieve its ends in the sensible sphere (i.e., the causality of a free will must , while the material world's organization must harmonize with free will/moral law such that the realization of those ends is possible. What Kant's looking for is, in a way, like the transcendental schema he identified in the first critique. There he was interested in the transition zone between intuitions and concepts; here he's looking for the one between concepts of nature and concepts of freedom (which, again, always reciprocally imply moral law).

Okay, then, we can guess where this is going. We see beautiful things in the world. Beauty stimulates our moral disposition and makes us more sensitive to our higher calling as rational agents. Good taste implies good character.

Or does it? Kant observes that "virtuosi of taste" aren't exactly renowned for their moral probity. I mean, sure: go to a high-profile gallery opening in New York and try to count the number of people in attendance who don't have some sort of personality disorder.

And so:

...it appears that the feeling of the beautiful is not only specifically different from the moral feeling (as it actually is), but also that the interest that can be combined with it can be united with the moral interest with difficulty, and by no means through an inner affinity.

Kant does indeed connect the beautiful to the good, though it takes him a while to get there, and he introduces a mountain of stipulations to the association.

|

| Caspar David Freidrich, Easter Morning (1835) |

He writes somewhat dismissively of the empirical or socially contingent interest in beautiful objects, coming to the conclusion excerpted (in part) above. A group of people with refined taste tend to be self-indulgent and vain (so says Kant, and I'm not sure I can argue with him), and the transition from aestheticism to moral interest is an oblique one.

He's more keen on an "intellectual" interest in beauty, specifically the beauty of nature.

Someone who alone (and without any intention of wanting to communicate his observations to others) considers the beautiful shape of a wildflower, a bird, an insect, etc., in order to marvel at it, to love it, and to be unwilling for it to be entirely absent from nature, even though some harm might come to him from it rather than there being any prospect of advantage to him from it, takes an immediate and certainly intellectual interest in the beauty of nature. I.e., not only the form of its product but also its existence pleases him, even though no sensory charm has a part in this and he does not combine any sort of end with it...

...since it also interests reason that...nature should at least show some trace or give a sign that it contains in itself some sort of ground for assuming a lawful correspondence of its products with our satisfaction that is independent of all interest (which we recognize a priori as a law valid for everyone, without being able to ground this on proofs), reason must take an interest in every manifestation in nature of a correspondence similar to this; consequently the mind cannot reflect on the beauty of nature without finding itself at the same time to be interested in it. Because of this affinity, however, this interest is moral, and he who takes such an interest in the beautiful in nature and do so only insofar as he has already firmly established his interest in the morally good. We thus have cause at least to suspect a predisposition to a good moral disposition in one who is immediately interested in the beauty of nature.

Is it any wonder why Kant was so popular with the German Romantics for a time? I'm sure that William Wordsworth would approve of Kant's remarks here, as would Wordsworth's superfan Alfred North Whitehead—who was very critical of Kant.

Kant's reasoning is a bit subtle here. He draws a line from the sensus communis and the subjective demand that everybody sees beauty where we see it to the categorical imperative, the format of the moral maxims, which would have us act in such a way that we would will everyone else to act, without taking benefits to ourselves into consideration. Kant implies that this isn't as often the case with manmade objects, insofar as our interest in them typically contains a social dimension, and thus a greater or smaller kernel of empirical self-interest.

Kant attaches this moral feeling with regard to beautiful things in nature to the appreciation of art to the extent that art can seem to be a thing of nature. On the one hand, Kant would appear to value sprezzatura in visual art—the impression that the artist just slapped some paint on a canvas in obedience to the exhortations of his soul, and wasn't thinking about theory, trends, or dollar signs, and also didn't agonize over its composition any longer than he had to. On another he's interested in genius—the sort of artist who paints, sculpts, writes poetry, composes music, etc., and can't communicate how he does what he does. The genius must be not only a virtuoso, but a natural. In the act of creation he must be like a bee constructing a wax hexagon, executing his work with both competence and spontaneity (i.e., not by copying by rote or methodically imitating the art of others—or, I'd hazard to add, imitating his own work).

Again, there's something to this. In my admittedly limited experience, I've found that academic theorists tend not to be excellent artists, and excellent artists tend not to be very systematic thinkers.

Kant attributes genius to the artist's endowments with regard to his faculties of imagination and understanding, but also adduces spirit, a property or a function belonging to the imagination. More precisely, he calls it a principle, and has this to say about it:

Now I maintain that this principle is nothing other than the faculty for the presentation of aesthetic ideas; by an aesthetic idea, however, I mean that representation of the imagination that occasions much thinking though without it being possible for any determinate thought, i.e., concept, to be adequate to it, which, consequently, no language fully attains or can make intelligible —— One readily sees that it is the counterpart (pendant) of an idea of reason, which is, conversely, a concept to which no intuition (representation of the imagination) can be adequate.

This is interesting! —is what I penciled in the margin beside this passage.

Kant introduced the word "idea" in the first critique, and assigns the term a special Platonic meaning. The main ideas of reason—the transcendent ideas—he treats have to do with the origin of the universe, the soul, and god. Did the universe have a beginning or has it always existed? Yes. No. It's a trick question. Nothing given to us in experience can determine the question one way or the other. (The prevailing theory of the big bang isn't a solution; the question then turns to the provenance of the cosmic egg. Did it always exist? If not, how and when did it come into being?) Or: is there such a thing as a soul? Where is it? What is it made of? Is it an irreducible substance, some point in space within us, or does it possess volume in some way? If we assert that I am my soul, aren't I just inserting an extraneous term into the statement? And so on. Ideas of reason are inferential illusions—concepts for which an empirical counterpart can never be found.

Aesthetic ideas are the inverse of ideas of reason. The imagination conjures a phantasmal image or a sensation that beggars conceptualization. The artist speaks of trying to approximate with oil on canvas the perfection that seems to exist in his mind. The poet strives to articulate something he doesn't know in verse, and which he hasn't the language to express otherwise. Speaking for myself: the origin of my first book, The Zeroes, was a feeling in my guts that I couldn't approach without writing a book, designing the narrative to activate that same feeling in the reader (and I tested its efficacy, repeatedly, on myself).

An aesthetic idea contains more than raw sensation or emotion; in most (all?) cases there's an intellectual component. Kant, who wrote the Critique of the Power of Judgement long before the likes of Kandinsky, Pollock, et al. redefined the criteria of visual art, never considered and doesn't countenance the notion that somebody could simply cover a large canvas in variegated shades of blue paint and say it expresses sadness. The power of beautiful art, he says, is to "give the imagination an impetus to to think more, although in an undeveloped way, than can be comprehended in a concept, and hence in a determinate linguistic expression."

There's an analogy with the supersensible here, is there not? The painter, poet, musician, etc. tries to reach beyond the wall of experience and approximate the form of what he discovers on the other side. In this regard an aesthetic idea isn't so different from an idea of reason as we might have suspected, since the concepts attached to them, while indeterminate, possess a purity than isn't to be found in the actual course of events. In praise of poetry, Kant says that the poet possessed of genius takes rational ideas and empirical experience as his raw material and...

...makes them "sensible beyond the limits of experience, with a completeness that goes beyond anything of which there is an example in nature, by means of an imagination that emulates the precedent of reason in attaining to a maximum...This faculty, however, considered by itself alone, is really only a talent (of the imagination).

The indirect relation between art and the supersensible is precisely why Kant nominates poetry as the greatest of the "beautiful arts" a few pages later:

It expands the mind by setting the imagination free and presenting, within the limits of a given concept and among the unbounded manifold of forms possibly agreeing with it, the one that connects its presentation with a fullness of thought to which no linguistic expression is fully adequate, and thus elevates itself aesthetically to the level of ideas. It strengthens the mind by letting it feel its capacity to consider and judge of nature, as appearance, freely, self-actively, and independently of determination by nature, in accordance with points of view that nature does not present by itself in experience either for sense or for the understanding, and thus to use it for the sake of and as it were the schema of the supersensible.

There it is: the supersensible. Wherever Kant uses this term, it's only a matter of time before he brings up morality and free will.

He also ranks painting higher than the other visual arts (architecture, sculpture, and, erm, the design of pleasure gardens) on the grounds that...

...it is the basis of all the other pictorial arts, partly because it can penetrate much further into the region of ideas and also expand the field of intuition in accordance with these much further than is possible for the rest.

Kant seems to employ a rather Platonic criterion for the value of an art form (notwithstanding Plato's willingness to banish poets from his ideal state).

|

| Caspar David Freidrich, Fir Trees in the Snow (1828) |

A bit further ahead, Kant gets down to brass tacks and identifies the singular principle of the power of aesthetic judgments as the idealism of the purposiveness of nature and of art. This is in opposition the possibilities of an empirical or a rationalistic principle of taste (or judgements of the beautiful), the first of which he dismisses out of hand: any distinction between the beautiful and the merely pleasurable would have to be arbitrary.

He waffles on the second option on the basis that rationalistic judgements require determinate concepts as their grounds, which aesthetic judgements lack by definition—though there are other grounds that are compatible with rationalistic principles, in spite of this. To make a long explanation short, he asks whether the principle of purposiveness is real or ideal—objective or subjective. I will confess that as I type this I wonder if I missed or misread something, because I thought we'd already established formal or subjective purposiveness as the grounds for judgements of taste.

But anyway, Kant begins settling the matter by accounting for the ideality in judgements of the beautiful in nature:

[I]n such judging what is at issue is not what nature is or even what it is for us as a purpose, but how we take it in. It would always be an objective purposiveness of nature if it had created its forms for our satisfaction, and not a subjective purposiveness, which rests on the play of the imagination in its freedom, where it is a favor with that which we take nature in and not a favor that it shows to us. That nature has an occasion for us to perceive the inner purposiveness in the relationship of our mental powers in the judging of certain of its products, and indeed as something that has to be explained as necessarily and universally valid on the basis of a supersensible ground, cannot be an end of nature, or rather be judged by us as such a thing: because otherwise the judgement that would thereby be determined would be grounded in heteronomy and would not, as befits a judgement of taste, be free and grounded in autonomy.

We can account of the ideality of art's purposiveness more easily. The aesthetic ideas underlying and expressed in works of art are "essentially different from rational ideas of determinate ends," and their purposiveness is not to be found in their contribution toward any mechanical application or practical end—after all, one of the most effective ways of smearing an artist is to accuse him or her of "selling out" and just churning out work for the sake of a payday.

And, at long last, Kant ties a string between the beautiful and the good by declaring the former a symbol of the latter. As usual, he has to explain precisely what he means by "symbol."

The representations of a concept, Kant says, can either be given by examples or schemata. If the concept is entirely empirical, we use examples; if sufficiently abstract, we must use schemata.

The symbolic is then a subdivision of the schematic. Schemata "connect" concepts that are given a priori to sensible intuition (Kant covered this back in the first critique), while in the symbolic presentation of a concept "which only reason can think," the power of judgement approximates the procedure of schematization as best it can. Kant cryptically explains:

[I]t is merely the rule of this procedure, not of the intuition itself, and thus merely the form of the reflection, not the content, which corresponds to the concept.

In other words: underscoring the first term in the phrase formal or subjective purposiveness. At any rate, a symbol presents the concept indirectly.

Now I say that the beautiful is the symbol of the morally good, and also that only in this respect (that of a relation that is natural to everyone, and that is also expected of everyone else as a duty) does it please with a claim to the assent of everyone else; in which the mind is at the same time aware of a certain ennoblement and elevation above the mere receptivity of a pleasure from sensible impressions, and also esteems the value of others in accordance with a similar maxim of their power of judgement. That is the intelligible, toward which...taste looks, with which, namely, even our higher faculties of cognition agree, and without which glaring contradictions would emerge between their nature and the claims that taste makes.

(All of this is eerily similar to Kant's remarks on moral feeling and duty throughout the Critique of Practical Reason.)

In this faculty the power of judgement does not see itself, as is otherwise the case in empirical judging, as subjected to a heteronomy of the laws of experience; in regard to the objects of such a satisfaction it gives the law to itself, just as reason does with regard to faculty of desire; and it sees itself, both on account of this inner possibility in the subject as well as on account of the outer possibility of a nature that corresponds to it, as related to something in the subject itself and outside of it, which is neither nature nor freedom, but which is connected with the ground of the latter, namely, the supersensible, in which the theoretical faculty is combined with the practical, in a mutual and unknown way to form a unity.

The supersensible has proven itself one of the most valuable tools in Kant's philosophical toolkit. In the liminal zone where the obscurity of noumena meets the light of reason does possibility dwell. The concept of freedom might be incompatible with theoretical reason, but the supersensible provides the inch of wiggle room from which Kant takes a mile. In the same way it secures the possibility that nature is more than the pointless agglutination of particles blindly and purposelessly scurrying this way and that.

In any event, sharing its ground in the supersensible with free will is what connects beauty and our capacity to perceive it with morality—which in the Kantian system is inseparable from the concept of free will. Taste is analogous with moral interest: we take pleasure in beautiful objects irrespective of any consideration of personal advantage, and that pleasure is immediate; the judgement of beauty is subjective, but universal; the perception and judgement of beauty is grounded in the autonomy of our faculties from causal contingencies. All of this has been established throughout the Critique of Aesthetic Judgement, and could just as well serve as a bullet list of points made in the second critique regarding pure practical reason—if some key words were swapped out.

Again, an interest in beauty doesn't necessarily translate into moral interest or feelings. Kant made that clear several sections ago:

...since the latter [objects of taste] indulges inclination, although this may be ever so refined, it also gladly allows itself to blend in with all the inclinations and passions that achieve their greatest variety and highest level in society, and the interest in the beautiful, if it is grounded on this, could afford only a very ambiguous transition from the beautiful to the good.

Nevertheless, Kant insists that the true purpose of taste is to judge (or perceive, or understand) material expressions of moral ideas. The Critique of Aesthetic Judgement concludes with the admonition that the most effective instruction in taste must be one that makes it more fit for this end.

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, The Sea of Ice (1824) |

The link between moral interest and the sublime is much more straightforward. Kant assays the sublime independently of his inquiry into beauty and taste, condensing the whole examination in a section (Analytic of the Sublime) nestled right in the middle of the Critique of Aesthetic Judgement.

When we say that something is "sublime," we usually mean something like "beautiful in a spiritual or transcendent way," or maybe "beauty squared." In the late eighteenth century, authors who wrote about taste had a much more specific meaning in mind, and might be inclined to slap somebody who'd use the word to describe something so frivolous as a bite of expensive cheesecake.

When Kant talks about the sublime, the feeling to which he refers is pleasurable, and yet typically accompanied by awe or fear. Violent events in nature, a sweeping vista beheld from the edge of a cliff, a seemingly illimitable expanse of desert or ocean—any of these might inspire a sense of sublimity. Situations that evoke such a feeling must necessarily leave you feeling dwarfed or physically threatened. Vanishingly few, if any, manmade artifacts are capable of it. Kant mentions the Egyptian pyramids and Saint Peter's cathedral, but only in an analogy. To his mind, the sublime is the exclusive province of nature.

The sublime is similar to the beautiful in that...

...both please for themselves...both presuppose neither a judgement of sense nor a logically determining judgement, but a judgement of reflection...both sorts of judgements are also singular, and yet...profess to be universally valid in regard to every subject, although they lay claim merely to the feeling of pleasure and not to any cognition of the object.

The big difference, however, is that the experience of the sublime is one of "negative pleasure"—because it accompanies occasions that leave us feeling diminished or even threatened, it doesn't elicit satisfaction so much as respect.

Like the musician playing a concert who rolls out a ten-year-old song that was never a single and nobody expected to hear again, Kant brings up the minor concept of mathematical and dynamical categories from the Critique of Pure Reason in analyzing the sublime. (Recap: the categories under the quantity and quality headings are mathematical; relational and modal categories are dynamical.) The feeling of the sublime, he says, has a mathematical and a dynamical aspect.

To make this short, we can boil down the mathematical aspect of the sublime to one of Kant's boldfaced sentences: "That is sublime in comparison with which everything else is small." This seems like it's easy to disprove. We experience the shudder of sublimity craning our necks to glimpse a mountain peak behind tufts of cloud; we know on an intellectual level that there are things in the world much bigger than this rocky protuberance; so what's the fuss about?

The sublime is a feeling, and has less to do with the object that inspires it than how we take it in. On this point, Kant differentiates between apprehension and comprehension:

There is no difficulty with apprehension, because it can go on to infinity; but comprehension becomes ever more difficult the further apprehension advances, and soon reaches its maximum, namely the aesthetically greatest basic measure for the estimation of magnitude.

(Remember that this is the late eighteenth century, and "aesthetically" just means "pertaining to sense perception.")

For when apprehension has gone so far that the partial representations of the intuition of the senses that were apprehended first already begin to fade in the imagination as the latter proceeds on to the apprehension of further ones, then it loses on one side as much as it gains on the other, and there is in the comprehension a greatest point beyond which it cannot go.

In other words, he's talking about taking in an object or scene that's so vast, and from such a vantage point, that it can't be grasped all at once. This is where Kant uses Saint Peter's cathedral as a metaphor, commenting on the "embarrassment" that one feels upon entering:

...here there is a feeling of the inadequacy of his imagination for presenting the ideas of a whole, in which the imagination reaches its maximum and, in the effort to extend it, sinks back into itself, but is thereby transported into an emotionally moving satisfaction.

BF Skinner might call this appeal to the intelligible operations of discrete mental faculties an "explanatory fiction"—but let's put that aside for the time being.

The significance on the mathematical aspect of the sublime can be boiled down to another one of Kant's boldfaced sentences: "That is sublime which even to be able to think demonstrates a faculty of the mind that surpasses every measure of the senses." The experience of the sublime brings to the fore our special status as rational agents: our senses fail us, but our powers of reason strive to overcome the inadequacy of the merely sensory, perceptual aspect of our being. We might feel a corporeal humiliation in the prospect of a mountainous vista beheld from a cliff. On the one hand, we appreciate that we can't appreciate the full extent of what's before us; we can't map out its spaces and all their contents for ourselves, except in the abstract. But the fact that we're capable of doing so in the abstract implies that our mental faculties transcend the capabilities of our animal senses. We can conceptualize not only the vast, but the infinite, even though the latter is something never actually given to us in experience.

The feeling of the sublime is thus a feeling of displeasure from the inadequacy of the imagination in the aesthetic estimation of magnitude for the estimation by means of reason, and a pleasure that is thereby aroused at the same time from the correspondence of this very judgement of the inadequacy of the greatest sensible faculty in comparison with ideas of reason, insofar as striving for them is nevertheless a law for us. That is, it is a law (of reason) for us and part of our vocation to estimate everything great that nature contains as an object of the senses for us as small in comparison with ideas of reason; and whatever arouses the feeling of this supersensible vocation in us is in agreement with that law.

"Supersensible vocation in us?" Do I hear an echo of the Critique of Practical Reason, which assigned the rational agent certain a priori duties on the supersensible grounds of free will?

If we don't mind fudging some of the particulars, we can sum up Kant's exploration of the dynamically sublime with a restatement of the mathematically sublime in which references to magnitude are substituted with references to power. The crushing force and roar of a waterfall, streaks of lighting illuminating the dark horizon in a thunderstorm, a brushfire sweeping across the plains—all of these might evoke sublimity, provided we have the luxury of a safe vantage point. (After all, panic and desperation don't leave us much bandwidth to appreciate the aesthetics of a violent event.)

Once again, the effect is to arouse the feeling of both being overawed and somehow elevated:

[T]he irresistibility of [nature's] power certainly makes us, considered as natural beings, recognize our physical powerlessness, but at the same time it reveals a capacity for judging ourselves as independent of it and a superiority over nature on which is grounded a self-preservation of quite another kind than that which can be threatened and endangered by nature outside us, whereby the humanity in our person remains undemeaned even though the human being must submit to that dominion. In this way, in our aesthetic judgement nature is judged as sublime not insofar as it arouses fear, but rather because it calls forth our power (which is not part of nature) to regard those things about which we are concerned (goods, health, and life) as trivial, and hence to regard its power (to which we are, to be sure, subjected in regard to these things) as not the sort of dominion over ourselves and our authority to which we would have to bow if it came down to our highest principles and their affirmation or abandonment.

This intersects with the reasons a lot of people give with regard to why they enjoy camping—and I mean really camping, roughing it, hiking three or four hours through woods and hills, pitching a tent, and subjecting themselves to the whim of the elements and the silence of the wilderness for two or three nights. It "puts things into perspective." We seem to discover the bedrock of our values during periods of privation, or in moments where we vividly imagine ourselves at the mercy of forces we can't control.

I'm going to end this here; I feel myself running out of steam, and there's still the Critique of Teleological Judgement to go over.

When it comes time to sum things up and actually contribute my two cents on all of this, I'll have more to say about Kant's remarks about the sublime. Even if Kant himself believes that the concept of the sublime in nature "is far from being as important and rich in consequences as that of [natural] beauty," it was much more immediately interesting to me than his study of taste. I'll save it for later.

No comments:

Post a Comment