I'm really and truly at a loss as to where to start with this one. Sam Kieth's cult comic is a rabbit hole if ever there was one.

Sam Kieth? Who's Sam Kieth? Well, he co-created Sandman with Neil Gaiman. True story. Look at the illustration credits for the book's first five issues. He voluntarily left the book because he didn't think his work was a good fit—and, frankly, he was right. But the fact stands that Kieth was responsible for Morpheus' visual design. He also did some work for Marvel, turning in some absolutely baller art for the Wolverine stories in Marvel Comics Presents, and did some Detective Comics covers for DC. So when he launched The Maxx in 1993, Kieth wasn't exactly an unknown in the industry.

We also need to acknowledge the contribution of William Messner-Loebs, whose previous credits included popular authorial runs on Wonder Woman and The Flash. Loebs acted more or less as The Maxx's co-writer and Kieth's editor for more than half the book's run.

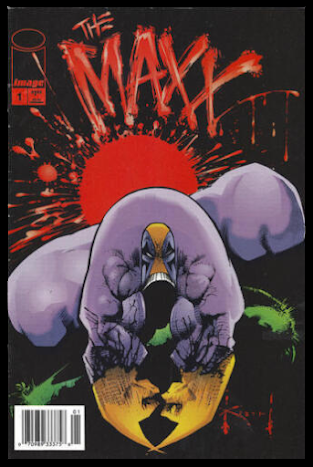

Let's begin with the cover.

We're at our local comic shop in 1993. We pick The Maxx #1 off the wall. We're conscious of the man behind the counter and feel his gimlet eye on us. As soon as we look at the interior pages, he's going to tell us that his store isn't a library and tell us to buy it or put it back.

Let's say that we also notice issues #3 and #4 shelved next to it. Maybe they'll gives us a clearer idea as to what The Maxx is about.

Let's say we decide to start at the beginning and pick up issue #1. What sort of comic book do we suppose we're taking home?

Well—it's 1993 and we're buying a comic with the Image logo on the cover. Perhaps you remember the Image exodus from Marvel? Todd MacFarlane got bent of shape because his editor wouldn't let him draw Shatterstar stabbing Juggernaut in the face, so he took his pencils, went home, founded his own comic book imprint, and invited his friends to join him.* Image is where MacFarlane launched Spawn, where Rob Liefeld landed after quitting X-Force, and where Jim Lee created his own MTV-generation teen superteam. We can realistically expect grit. We can expect blood. We can expect sensational Mature Situations.

* I actually had a copy of that one when I was a kid. Spider-Man #16, November 1991. That was the one where Juggernaut knocked over one of the Twin Towers. In a world where New York had suffered a full-scale demon invasion just a little while ago, something like half of a 9/11 wasn't really that big a deal.

What do we make of the man on the cover? Do we think he's majorly wicked, or do we find him silly?

The early-to-mid 1990s were a strange time for superhero comics. There was no such thing as over-the-top. The satirical intent in stuff like DC's Lobo and Marvel's Punisher 2099 soared over their readerships' heads; after all, there were scores of other titles doing pretty much the same thing, but without a trace of irony. On the basis of The Maxx #1's cover, it's impossible to guess whether we're buying an earnestly EXTREME RADICAL ASSBAD 1990s superhero book, or something a bit more puckish.

So here we have the Maxx in his first interior appearance. Should we be surprised that Kieth was less known for penciling a few issues of Sandman than for drawing Wolverine and the Hulk?

Judging from appearances, the Maxx is a superhero. Obviously. This is an American comic book, the character has a sobriquet instead of name, and he's a huge mother wearing a costume that conceals his face. He ticks too many boxes not to fall under the "superhero" category.

Notice that in the image above he's emerging from a cardboard box to menace a street tough. The Maxx sleeps in that box.

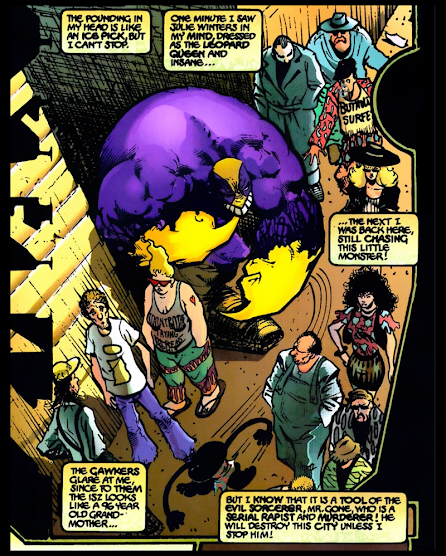

The Maxx has a lot in common with the Dark Knight Returns' version of Batman. For one thing, look at him. He's more beef than man. And he doesn't have a good relationship with the city police, either: Johnny Law thinks the Maxx is just a crazy bum. And, like Frank Miller's take on the Caped Crusader, the Maxx delivers a lot of hardboiled monologues via narration boxes—except these don't convey the Maxx's private thoughts, because he's actually speaking out loud the whole time. The Maxx isn't excruciatingly bright, and often finds himself confused by what's happening to him.

Okay, so it looks like maybe the The Maxx got caught in the late 1980s "deconstruction" wave. He thinks he's a superhero, but he's just a bulky, mentally ill weirdo with who occasionally beats up criminals. Sure. So The Maxx is a satirical superhero, right?

...Right?

A better question would be: is the Maxx pretending to be a superhero, or was Sam Kieth pretending to do a superhero comic?

At least for the first several issues, Kieth and Messner-Loebs seem like they're trying to give the early-1990s comic book market what it wanted, which was gritty and occasionally over-the-top superhero stuff. Having earned readers' plaudits by drawing

the grittiest Wolverine ever, Kieth probably felt saddled by the expectations of a personal brand—and besides, the last time he'd worked on a non-superhero titled (

Sandman), he proved an awkward fit.

And so the book and its titular character both try to play the part. In issues #2 and #3 the Maxx trades blows and dialogic barbs with his debut arch-nemesis. In issue #6 he brawls with Mako, a villain associated with Image hero Savage Dragon. In the following issue he teams up with Pitt, the titular character of Dale Keown's Image series. Messner-Loebs was reportedly more into this genre-standard material than Kieth, whose cognitive dissonance about doing a superhero title is increasingly palpable as the series continues.

Issue #4 has the Maxx fighting his bête noire's hench-creatures, but the action scenes are all just incidental to the introduction and character study of Sarah, a troubled teenager and aspiring author. Issue #5 has the Maxx getting pulled into a cartoon otherworld illustrated by his cousin David Feiss (who later created Cartoon Network's

Cow and Chicken), where everyone speaks in Dr. Suessian rhyme. Even the crossover with Pitt is more like

the issue of the

Ren & Stimpy comic where Spider-Man fought a mind-controlled Powered Toast Man than a for-serious super team-up.

The Maxx's delusions afford Kieth some authorial latitude to follow his own flights of fancy. It's established early on that the Maxx is a disordered homeless man (with some degree of superhuman strength and durability) in a mask and purple costume, providing a built-in excuse for the book to take detours into Saturday morning cartoons, and for the vaudevillian aspect of the fight scenes. But even from the beginning, there's an emergent method to the madness.

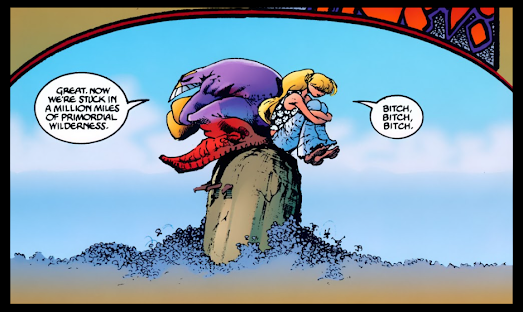

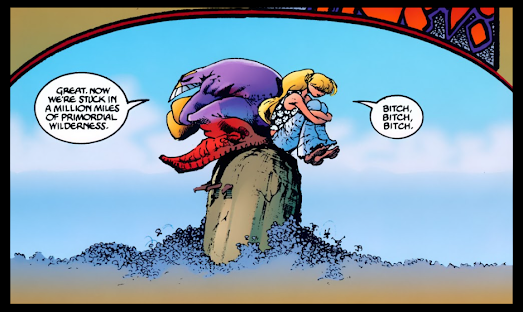

When the Maxx loses his grip on reality, he finds himself in a primordial wilderness called "the Outback." Here he's an aboriginal warrior wearing a feathered headdress, and he must navigate a hazardous landscape teeming with bizarre cryptids. Visions of the aloof and mighty Leopard Queen haunt him in the Outback, and inspire him to be a hero.

The Leopard Queen bears an uncanny resemblance to one Julie Winters, who helps out the Maxx when he gets dragged off by the police for fighting and destroying property. She's a social worker; he's a delusional homeless man who gets in trouble with the police. It's her job.

Although—Julie doesn't treat the Maxx like her other clients. She becomes more of a friend to him. But she doesn't seem to mind taking that kind of responsibility for him. For one thing, he's a lot nicer than most of her other clients.

We also meet Mr. Gone, a self-styled sorcerer who's sojourned in the Outback. He brings some of its creatures—the semi-intelligent, magically camouflaged, carnivorous "isz" species—into the city to do his bidding, most of which involves trying to kill off the Maxx and harass Julie.

Mr. Gone knows thing about them. Dangerous things. Cryptic things. Foreshadowy plot-thickening things.

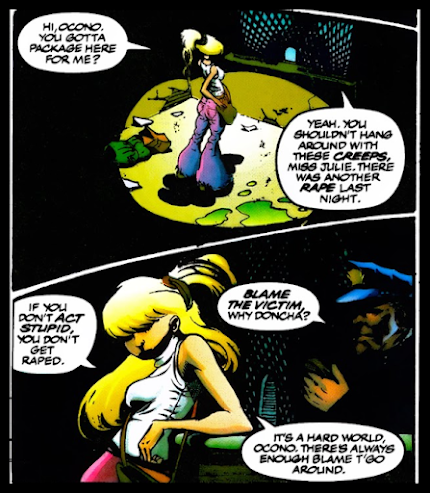

The Maxx doesn't sugarcoat Mr. Gone's proclivities. He's a serial rapist.

Julie Winters has opinions about rape.

Julie is guilty of callousness, but not ignorance. Some years ago, when she was studying to be an architect, she pulled over to help a man who pretended to be having car troubles. He beat her up, raped her, and left her for dead. She's totally over it, though. Completely.

Yessiree.

Okay—I've got an idea. I'm not going to try to summarize the plot. That's better left to the professionals. The opening to the comic's thirteen-episode television adaptation (produced and aired during the brief but brilliant flowering of MTV Animation) sums up what the whole thing's about in a monologue, delivered by Mr. Gone, which opens up each episode.

Most of us inhabit at least two worlds: the real world, where we are at the mercy of circumstance; and the world within, the unconscious, a safe place we where can escape. The Maxx shifts between these worlds against his will. Here, homeless, he lives in a box in an alley. The only one who really cares for him is Julie Winters, a freelance social worker. But in Pangaea, the other world, he rules the Outback and is the protector of Julie, his Jungle Queen. There, he cares for her. But he always ends up back in the real world. And me, old Mr. Gone? Only I can see that the secret that unites them could destroy them. I could be helpful...Ah, screw it! I think I'll have some fun with them first.

If I could link to a video of this, I would. It's not on YouTube. It's not even on Vimeo. If you want to see it, you're on your own.

Julie reasonably assumes that the Outback is a product of the Maxx's unhinged imagination. If so, then she's drawn into a folie à deux when she gets pulled into in the Outback with him—and discovers that it's all somehow familiar.

Turns out the Outback isn't the Maxx's fantasy: it's Julie's, the inner world she built up as child, based on her Uncle Artie's stories about his time in Australia. For reasons that we can't even begin to articulate without a heap of exposition, the Maxx has been made a simultaneous resident of a sordid, corrupt urban reality and of Julie's personal dreamtime, where he recognizes her as the Jungle Queen she pretended to be when she was a little girl.

And Julie's Uncle Artie, incidentally, was a practitioner of the mystic arts who's lately calling himself Mr. Gone. Although, actually, Mr. Gone might not be the actual Uncle Artie, but a magical projection whose reality is colored by the perceptions of a third party who also has some history with him...

Oh, darn it. I'm synopsizing again.

We can split The Maxx into two volumes. One runs from issues #1 through #20 and deals with the Maxx and Julie Winters. The second runs from issue #21 to the series' end at issue #35, and deals with Sarah—after a ten-year time skip.

Summarizing the first twenty issues is a messy proposition, and doesn't do The Maxx justice. There are a few reasons for this.

The first is that Kieth and Messner-Loebs (but especially Kieth) were flying by the seats of their pants. Judging from some of the dialogue between the Maxx and Mr. Gone, Kieth had some idea of where he wanted to take the story, but was still making it up as he went along. He introduces ideas and plot threads with a lot of dramatic intrigue, and either quietly negates them or produces some conceptual contrivance to splice them together later on. (The early "revelation" that the Outback is the real world and the city is Julie's dream is a particularly salient casualty of the book's improvisational plotting.) In several issues, the Maxx and his escapades either act as a pretense for some quodlibetical tangent that interests Kieth more than superhero schtick or advancing the plot, or are altogether jettisoned in favor of a side story. (The Maxx doesn't appear at all in issue #13, which follows two separate threads about Sarah's body issues and her grandfather's attempts to escape from his nursing home.)

When the The Maxx gets purring along, it's not so much a linear journey as an analytical one. We have the Maxx, Julie, Sarah, and Mr. Gone. They do things with and to each other, and therein consists the book's plot. But the real story isn't so much about moving forward, but going deeper (in order to move forward). The depictions of events occurring in time function as a machine that peels back the layers of history, trauma, messy interpersonal relationships, and mystical woo to uncover The Truth. At its heart, The Maxx's first volume is an unorthodox Jungian therapy session that just happens to feature a Wolverine/Hulk pastiche tromping around in a purple bodysuit.

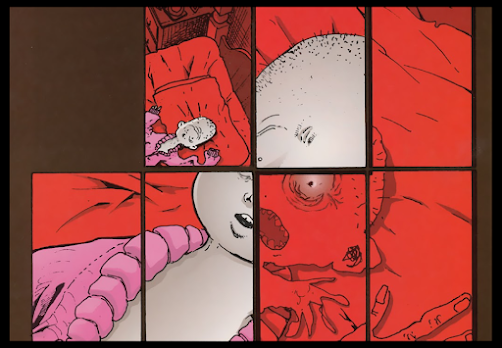

But what makes such an unseemly endeavor of boxing The Maxx's "Julie" arc into a few blurbs of synopsis is that it's an illustrator's book—a realization of Image Comics' promise to turn over control to comic artists. That Sam Kieth is an artist first and a writer second is obvious from the outset. This isn't the work of someone who thinks of the comics page in terms of sequential boxes containing pictures and words (as do most authors when they write a script for an illustrator to follow), but as a unified whole. Kieth routinely draws oversized eye-popping panels and experiments with layouts, and the results can be extraordinary—though it also makes pulling images for this writeup a real bitch, what with all the giant, irregularly shaped panels, panels within panels, objects and word balloons/boxes crossing borders, and unusual formatting. (My favorite instance is below: several pages from issue #20 are framed by two full-height vertical columns depicting Julie Winters and the Leopard Queen making contact.)

The point is, The Maxx is tough to talk about as a trip from Point A to Point D by way of Points B and C. Sam Kieth, like any excellent visual artist, isn't a linear thinker. That was the reason he asked Messner-Loebs to be his co-author; he needed someone to help him process and format his ideas, and even with Messner-Loebs' input, The Maxx is still all the hell over the place. The reader following the story as it advances forward in time and delves deeper into its characters' lives isn't asked to follow a thread so much as apprehend the structure of a woven mesh.

The credits page at the beginning of

The Maxx's second volume, issue #21, conclusively disqualify the title from being categorized as a superhero book. Messner-Loebs had left the book, and for a single issue his role was filled by none other than Alan Moore. And if Alan Moore had gotten even the faintest whiff of "superhero" from

The Maxx, he would have kept his distance.

In volume two, The Maxx abandons every last trapping of a superhero comic and leans into magical realism.

I wonder whether it was Kieth or Moore who came up with the explanation of Mr. Gone's name. When a grown-up Sara (who's dropped the "h" in her name) tracks him down to a trailer park and goes knocking at his door, we discover his real name is Artie Pender. He's in his mid-to-late sixties now, and more or less harmless. Back when he was a serial-rapist sorcerer who menaced Julie and the Maxx (before switching over and becoming Julie's devilish guide), it seems that version of him was an avatar, a projection he broadcast from a distance. (Like so much else in The Maxx, this isn't altogether consistent with later events and revelations, but this is a book where this kind of thing matters less than you'd think. Nonlinear, magical thinking doesn't archive its receipts.)

"Magical forms are more like a language than individuals," Artie explains to Sara. "They're like letters from some alien alphabet. So much depends on how you interpret them."

This, he claims, is why he has no recollection of going by the name "Mr. Gone." Apparently Sara's perception of him colored certain aspects of his appearance, including his name for himself.

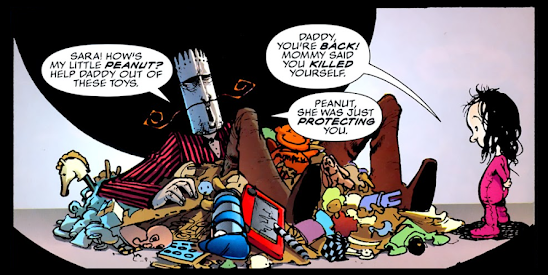

We know from issue #4 that Artie left Sara behind when she was "too young to remember." Her mother told her that he killed himself. Turns out, that was a lie—Sara's mom didn't want to tell her that her daddy had a history of sexually assaulting women, and asked him to leave when she began to fear for her (Sara's) safety. Sara never got over the loss.

And so he became Mr. Gone. The man who isn't there.

Sara's arc more or less takes up the remainder of the book's run. (I say "more or less" because the train willfully jumps the track towards the end—but we'll get into that later.) All is not well in Sara's personal Outback. A banana slug named Iago that slipped into the real world ten years ago has grown to monstrous proportions and gone on a rampage. She allies with her own Maxx—Norbert the horse—to put a stop to the carnage, but they can't do it without getting some help from Artie.

Once again the story is about a female character confronting her trauma. Iago is the incarnation of all the grief and rage Sara suffered ever since her dad left, and it's been going around and murdering everyone who was once important to her in a twisted expression of his progenitor's abandonment issues. Sara's relationship with her estranged father becomes the emotional thrust that gives the second volume its forward momentum. Even when he was Mr. Gone, Artie's paternal affection for his daughter shone through his sardonic malevolence, and he desperately wants to reconnect with Sara. Understandably, Sara isn't thrilled about having a psychic voyeur and serial rapist for a dad, no matter how sweet and cute he comes across now that he's "retired."

The Maxx's second volume doesn't quite reach the heights of the first. Kieth has grown as a writer, which may account for why the pages take on a less ambitious, more familiar grid format: now that he's the sole author, he has to think of the page in terms as the vehicle for a script. (It may also be that he was losing his zest for the work, but we'll get into that in a minute.) Even so, without the influence of the more seasoned Messner-Loebs, Kieth struggles to keep things on an even keel. Issues #21 through #35 aren't bad. They just aren't equal to the tour-de-force of issues #1 through #20.

Issue #26—titled "The Origin of Mr. Gone"—compensates for every other area in which the book's second phase falls short of the first.

I won't go into detail, except to say that Mr. Gone's story is of the cycle of abuse. The Maxx #26 is one of the most wrenching, raw, and real issues of a comic book I've ever read. It makes Moore's epochal origin story for the Joker in The Killing Joke seem like a Saturday morning kiddie matinee by comparison—although, since we've established that The Maxx isn't a superhero book, we're comparing apples to oranges here.

As often as The Maxx indulges in off-kilter humor, deviates into fanciful and/or creepy tangents, and plays fast and loose with its own continuity, the whole thing is held together by the thematic ligature of trauma. Julie was raped.* Sara lost her dad. Artie was raped, became a rapist, and has to live with a past he can't escape from and a shadow he can't exorcize from himself as he tries to reconcile with his beloved daughter.

* It should be mentioned that ground zero, the pivotal moment in which something vital inside of Julie was shut off (setting up her long-term response to a very bad night) happened much earlier in her life, and had nothing to do with sexual abuse. I can't see into Kieth or Messner-Loeb's heads, but I'd like to think this shows some genre-savvy deliberateness on their parts. Julie's narrative goes deeper than "it all began with a rape"—although for the purposes of a glancing review, it's more convenient to highlight the traumatic event we can a put a one-word name to than the very particular set of interlocking events that scarred her as a child.)

Julie, Sara, and Artie are The Maxx's true protagonists, the people whose journeys of discovery and reconciliation constitute the real meat of the book. Meanwhile, both of the characters called the Maxx are like Shakespeare's Cymbeline, titular figures playing third fiddle. Norbert the horse, who acts as the Maxx of Sara's Outback, appears as a one-dimensional guide and protector. As the first arc came together, it turned out that Julie's Maxx was an innocent bystander supernaturally thrust into the role of her spirit animal, and can't become a complete, autonomous person until he helps her sort out her inner life. He's the genderswapped version of the female sidekick who solely functions to help the male hero complete his journey, and discovers that it's a pretty lousy position to be in.

This wasn't by design. Kieth obviously believed he needed to do a male-centered superhero comic if he wanted to sell copies, and The Maxx outgrew that conceit in short order. I wouldn't be surprised if the reason he introduced a new Maxx (one that doesn't even try to look like a costumed super-character) to accompany Sara is because he worried about the awkwardness of selling a book whose namesake had walked off the set.

Looking at the covers from the Julie arc, you probably wouldn't guess that The Maxx isn't really a superhero comic, and you definitely wouldn't suppose it's a book about women. The first issue introduces Julie as a social worker who dresses "like a hooker" and whose amazonian alter-ego poses in a leopard-fur bikini, but this probably came out of Kieth's early efforts to give his imagined audience what he thought it would spend money on. Once he comes into his stride and grows a bit more confident about telling the kind stories he wants to tell, The Maxx becomes not only a book about women, but one that would almost certainly pass muster under evaluation from a hard feminist lens—even though it would pose a few challenges. If I hadn't seen the credits pages and you asked me whether I thought its writer was a man or a woman, I'd probably venture to say there must have been at least an occasional female co-author, or a guest writer for certain issues. (Although as a man I might not be the best judge of this sort of thing.)

I was just about to say that The Maxx is at its best when it's dealing with emotionally vulnerable moments between its flawed and damaged characters, or quietly examining their fears, insecurities, and efforts to either push through or avoid confronting them. "It's a really human book," I might have said.

But maybe that's not it. Maybe the book reaches its local maxima when Kieth lets his imagination and pencil run wild and delivers us into the ecotones where inner and outer reality overlap, and introduces us to its indigenous cultures, dangerous wildlife, and bizarre environmental dynamics. Maybe it's at its best when it becomes a horror book. Or a mystery book. Or a comedy book. Since fans tend to agree that issues #1 through #20 outshine issues #21 through #35, maybe the pseudo-superhero stuff counts for more than we think...?

The Maxx's greatest accomplishment is being exactly what it is. I've never read another comic book like it. The only objects of comparison that come to mind are any number of "underground" black and white comics from the 1980s and webcomics from the early 2000s, but only insofar as none of them quite seemed to know what they were doing and were exceedingly messy. The Maxx turns this into a strength: since it never reaches a point where it becomes satisfied with itself, it never really exits that "seasons two and three" phase to coast on a reliable and practiced method.

I read

The Maxx all in one night some time ago, and afterwards found that a superfan with the YouTube handle JerkComic had put out an eight-hour video series called "

How The Maxx Broke Sam Kieth." I'll confess I've only jumped around through it—it's

eight hours long—but it helps to explain how the comic became what it is. This isn't the place to recapitulate the stories of the behind-the-scenes drama and bullshit that plagued Kieth to the point where he finally said "fuck it, in issue #35 Mr. Gone casts a spell that rewrites the timeline and puts an end to all this shit," but it will suffice to say that it seems Kieth worked on

The Maxx in a perpetual state of discomfort, placing the book in a condition of ongoing reevaluation and evolution.

My initial thought about Kieth adopting a more conventional comic book layout in the later issues was that as he began to approach the work as its sole writer, having to script issues in advance made him look at the page as the linear medium for delivering that script. (This isn't always the case, but as the series nears its end, there are many fewer pages that look like the one directly above and many more that look like the one directly below.) It might also have been that he was tired and bereft of the early enthusiasm and hunger which brought him to give 110% to illustrating every page as a single, integrated composition. Issues #30 through #34 use the main plot as a framing device for self-contained side stories, and JerkComic adduces these as evidence of Kieth's desperation to get the hell away from The Maxx, its characters, and their stories.

The Maxx bears such an inexorable imprint of its artist/author that it remains completely true to itself even when it's conscientiously trying to escape from itself. When I came to this point in the book, I didn't bat an eye. Nothing seemed amiss, except I found it odd that Kieth would go off on a series of unrelated tangents right as the comic was coming up to the end. Had I not known that there were only five issues to go, I wouldn't have guessed for a moment that Kieth might be running out of steam and waffling on the question of whether to reboot the comic into a more suitable vehicle for the stories he was interested in telling and the pictures he was interested in drawing, or end it altogether.

I don't think I can go on like this. Trying to write about The Maxx at a digestible mid-length, and to an imaginary reader that has no prior familiarity with it, is like describing an acid trip to someone who's never taken one. Not only are you trying to relate events that they really needed to have been there for, but there's also nothing in their experience you can analogize them to. How do you write about a comic book that doesn't fit into any genre, resists comparison to anything else, and doesn't seem to understand itself half the time? I'm realizing that this is book that either needs a more academic treatment than I'm prepared to give it, or should just be a quietly acknowledged source of inspiration for a soul-delving artistic clusterfuck of one's own.

Having recently reread Adorno and Horkheimer's landmark essay on the culture industry, it's comforting to see a product of mass culture put a lie to their words. If we believe Adorno, The Maxx shouldn't even exist. It should have been a by-the-numbers superhero comic, or a by-the-numbers superhero satire, or a by-the-numbers magical realist Vertigo comic, or else it should have been rejected like an invasive and unwanted thought in the consciousness of the comic-consuming public.* Kieth was a rare mutant genius who tried and failed to conform to the program, and through a freak of circumstance, produced a mold-breaking opus in spite of himself.

* Maybe Adorno and his account of the culture industry still get the last laugh in explaining why The Maxx was so swiftly and so thoroughly forgotten, despite being enough of a hit to spawn a merchandise line and an MTV series.

It seems futile to wish for more comics like it—ones that are at once so utterly unlike anything else, and yet so obviously superb in terms of whatever metric we have to borrow or invent to judge them by. But The Maxx proves that they're possible.

Long term lurker/reader here, just wanted to chime in and say I've quite enjoyed this little series of comics talk you've done so far, hope there's more to come! Haven't read either series yet myself but very tempted now but Shade behind an extra paywall at the DC universe collection is majorly disheartening.

ReplyDeleteI got at least one more coming. Depends on how fast I can turn it/them out. The more the weather improves, the more I want to write my own stuff instead of doing writeups about stuff that's already out there.

DeleteI can't believe there is someone else who has even heard of the MAXX, let alone read it. I have never actually met another human being that knew of its existence. For me it was extremely disturbing. As someone who experienced some bad stuff as a child I can say that it was traumatic in a way that is almost impossible to describe to someone who hasn't lived it.

ReplyDeleteSometimes there's a level of representation by a creator that is too uncanny. This is one of them and it's one of two things; One, Keith had experienced it himself and was drawing on that experience. Two, he is such a creative mind that he was able to put himself in the place of such a trauma victim to the extent that he channeled that authentic trauma from the collective unconscious and acted as a conduit, representing in graphical form.

Based on what you said (and the title of that youtube video, which I have not watched), I believe it to be the latter, which would explain why writing this was damaging to him to the point of breaking (if that assertion is true). Had be experienced this it would more likely have bene cathartic as most other first hand experiential creators say is the process.

There have been a few other works that have impacted me like this, but the MAXX stands out in my mind.

I

Kieth has an incredible talent for vanishing into his characters' heads.

DeleteHey.

ReplyDeleteI have been reading your stuff for several years already, during most of that time I have remained silent but today I write a comment to Say Thank You.

Around twenty years algo I had to do weekly visits to the dentist, it was a pain and bothersome. But I remember going with a smile because My dentist had a Pretty Big collection of cómics in the waiting room, so I spent most of My visits sitting there reading wathever interesting stuff I was able to find.

In one of those times I found the maxx and read several numbers of the cómic. At the time I was a child with just enough understanding of English to play Pokémon so I barely understood any of the story and yet the memories of those chapters have been burned in My brain for years.

Along the years I forgot the name of the weird cómic about the purple guy and Blonde lady who were conected though their inner versión of Australia. And just when I thought I would never remember your post Made me remember about the maxx. A Pretty weird cómic but also one worth remembering.

Once again, Thank You and sorry for the lousy English.

Happy to be of service!

Delete